Dating the Synoptics:

Mark in the early 70's CE,

Luke and Matthew in the early 80's CE

Overview

When did Matthew, Mark and Luke write their respective gospels? Since they show a detailed, complex relationship with each other, they can only be dated in light of each other. To determine that dating, let's consider that relationship then we can looked into the date of their publication.

A. Relationship between the Synoptic Gospels

Scholars group the gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke together because they share the same narratives and sayings. In other words, they have the same outlook; hence, they are called the Synoptics (from the Greek, meaning "same viewpoint"). Because of their similarities, scholars try to see the relationship between the three, comparing and and contrasting their contents.

Three details stand out. First, we can find much of Mark in Matthew and Luke, in some cases almost word-for-word. Second, we can also discover an entire list of sayings common with Matthew and Luke (again, almost word-for-word) not shared with Mark. Finally, Matthew and Luke have materials (especially beginnings and endings) exclusive to their individual gospels. These tensions have led to several schools of theories about the development of the gospels.

1. Straight Line Theories.

Matthew - Mark - Luke

Traditional

Straight-line

Theory

Tradition proposed the classic straight line theory that influenced the canonical order to the gospels we find in the New Testament. In his De Consensu Evangelistarum 1.3-4, St. Augustine (354-430 CE) proposed the priority of Matthew because he held that the gospel was not only written for Jewish Christians; the evangelist first composed it in Hebrew, then it was translated into common Greek. Augustine then held that "the church of Christ has spread are regarded to have written in this order: first Matthew, then Mark, third Luke, and last John" (De Consensu Evangelistarum 1.3), where Matthew focused on the "kingly lineage" of Christ, Mark abbreviated Matthew but Luke wrote later concerning himself with "the priestly lineage." Hence, we have the straight line theory from Matthew to Mark to Luke (or Mt-Mk-Lk).

Augustine argued for sequence based upon thematic, not linguistic, considerations. But, modern scholars have many more tools to analyze the books than the venerable Church father had.

Reversing the order that gave Luke priority (Lk-Mk-Mt) fared no better. In either the case of Mt-Mk-Lk or LK-Mk-Mt, reducing the larger gospels of Matthew or Luke to the smaller Mark, then expanding to the remaining gospel presented multiple problems. One could reasonable expect both a refinement of wording and grammar. He could also expect to see an evolution in shared narratives. However, Luke's elegant Greek or Matthew's tightly written passages appeared degraded when we compare it to Mark's wooden word usage. The notion of episodic evolution fell apart with Mark's lack of an Infancy Narrative and his critical stance against Jesus' family, just to name a few examples. Ultimately, neither straight line theory could answer the problem of the verses shared in Matthew and Luke but not in Mark (detail 3).

2. Conflation Theory: Greisbach Hypothesis

Matthew - Luke - Mark

Greisbach's

Theory

In the late eighteenth century, the noted scholar, Johann Jakob Griesbach promoted a theory that Matthew, then Luke, fed Mark; in other words, (Mt to Lk) to Mk. He saw the interplay between the verses these three gospels share where Mark agreed with Matthew's account at times, then Luke's. He also noticed the obvious lack of major sections from Matthew and Luke like the Infancy Narratives, teachings like the Sermon on the Mount/Plain. He concluded that Mark edited his gospel to emphasize Jesus as the great teacher and to pare it down as a convenient catechetical tool, not unlike the "small" catechisms of the Reformation and post-Reformation eras.

In the end, while Griesbach's thesis did solve the problem of shared verses between Matthew and Luke (detail three), his thematic explanation of a smaller Mark proved as unsatisfactory as Augustine's. Griesbach proposed a reason for a small gospel that the text did not justify. Hence, scholars considered other theories.

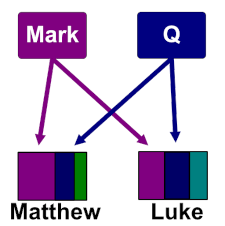

3. Branch Theory: The Two Source Hypothesis.

Two Source

Hypothesis

Scholars sought to overcome problems with the straight line and conflation theories by proposing one or more sources influenced the other two. A majority of scholars today have adopted the view that Mark influenced Matthew and Luke (detail one). However, another group of verses they call the "Q" (from the German "quelle" meaning "source") made its way into Matthew and Luke independent of Mark (detail two). This allowed both Matthew and Luke to develop passages independent of each other (detail three).

a. Priority of Mark

In his book "Q, the Earliest Gospel," John S. Kloppenborg argued for the Two Source hypothesis where Mark and the "Q" fed Matthew and Luke, a situation we can shorten to (Mk and Q) to (Mt or Lk). He based his reasoning for the priority of Mark upon the following observations:

1) A strong agreement existed between Mark and Matthew-Luke, both on a verbatim level and on the order of episodes. Verses agree in some cases word-for-word not only in important statements from Jesus but even in insignificant details. The flow of particular episodes also matched closely between Matthew and Mark in some cases, Mark and Luke in others and finally all three gospels. This agreement reached down "to the inflection of words, word order and use of particles" (Kloppenborg, 4)

2) The relative order of the episodes themselves found in the three gospels agree for the most part. Matthew 3-13 and Mark disagree in order, but agree from Matthew 14 onward. Overall, Luke and Mark agree in order.

3) However, when all three gospels reported a common narrative or saying, "it is relatively rare to find Matthew and Luke agreeing when Mark has a different wording" (Kloppenborg, 5). The same could be said about the details of a narrative. Matthew and Luke commonly disagreed with each other about wording and details in particular periscopes but not against Mark. In other words, Matthew and Luke drew upon Mark but edited his passages to suit their individual styles.

The first two factors support the view that the three gospels had a strong literary relationship. In other words, the gospel writers copied directly from a source. The third factor argued for Mark as the source Matthew and Luke shared, independent of each other. Mark was the common root the other two drew directly from.

b. "Q" Source: Passages Shared by Matthew and Luke Not in Mark

Kloppenborg championed the "Q" hypothesis, a common source for the verses Matthew and Luke share. However, the two evangelists drew from this source independent of each other. According to the scholar, this set of verses agree verbatim from "96 percent to less than 10 percent" depending on the passage. He maintained that in many cases, the verses agreed so much, both in vocabulary and the sequence of words, that the source must have been a common document, not just "bits of oral tradition." Even in shared passages where vocabulary and word flow vary between Matthew and Luke, they agree thematically, even using the same key words or phrases (Kloppenborg, 13-14).

Kloppenborg supported his contention with three factors. First, Matthew and Luke might disagree with each other but almost always agree with Mark's wording. And, when they move a particular Marcan passage, they never place it in the same location relative to each. In other words, they edit Mark independently.

Second, Matthew and Luke almost never placed their material ("Q" verses) in the same context relative to Mark. While some of these verses agreed in some cases word-for-word, each evangelist employed them in different settings to give them different shades of meaning. The only exceptions to this rule were two of the so-called "Mark-Q overlaps" where Matthew and Luke expanded upon Mark's narratives: 1) the preaching of the Baptist in Mk 1:2-6, Mk 1:7-8, Mt 3:1-2, Mt 3:7-10, Mt 3:11-12, Lk 3:2, Lk 3:7-9, Lk 3:16-17, and 2) the Temptation in Mk 1:12-13, Mt 4:1-11, Lk 4:1-13.

Third, when we compare the shared verses found in Matthew and Luke together, but remove any connection to Mark, they line up in the same relative order. These verses account for 35 of the 92 "Q" periscopes, about forty percent.

So, Kloppenborg held Matthew and Luke edited Mark separately, based upon 1) differences in the cases where they moved Mark's periscopes and 2) differences in the placement of their shared ("Q") verses to varied contexts (except for the Baptist's preaching and the Temptation), yet, he held the shared verses inferred a common source outside either evangelist, 3) pointing the same relative order of those verses when stripped of Marcan connections. Hence, he concluded a prior document existed we commonly call the "Q" source.

c. Passages Exclusive to Either Matthew or Luke

Those who hold to the Two Source theory point out the relative freedom of Matthew and Luke to develop individual passages to support their respective themes. I should remark that the evangelists could have employed separate oral traditions when they wrote these periscopes and not just invented the stories whole cloth. From a purely historical standpoint, the question remained open.

4. Reviving the Conflation Theory: Farrer's Hypothesis

Mark - Matthew - Luke

Farrer (Goodarce)

Theory

In 1955 scholar Austin Farrer published a paper proposing Mark as a primary source for Matthew and Luke, but then Luke employed Matthew as a source, thus eliminating the need for the "Q"; in other words, (Mk to Mt) to Lk. Mark Goodarce, one of the most recent supporters of Farrer's thesis, held Luke used Mark as a primary source because the evangelist used the shorter gospel, copying both wording and sequence almost intact (detail one). He pointed out that Luke employed Matthew as a secondary source, sometimes closely (word-for-word; detail two) and sometimes as inspiration for independent passages (like the Infancy Narratives: detail three). When Luke hued to Matthew closely, according to Goodarce, he suffered from writer's "fatigue" while he flashed editorial brilliance when he rearranged Matthew's verses and even wrote narratives independent of Matthew. Of course, Goodarce implied, Luke exercised his considerable writing skills on a spectrum between copying and weaving new material into his narrative whole cloth. Overall, Goodarce insisted positing the "Q" source was unnecessary; Luke's dependence on Matthew solved the problem of the hypothetical extra source.

Scholars like Goodarce objected to the Two Source theory on two grounds: 1) evidence clear existed that Matthew and Luke agreed in wording against Mark and 2) no historical evidence existed for the "Q" document (argument from silence). As the Wikipedia article on the "Q" source stated:

"...there are 347 instances...where one or more words are added to the Markan text in both Matthew and Luke; these are called the "minor agreements" against Mark. Some 198 instances involve one word, 82 involve two words, 35 three, 16 four, and 16 instances involve five or more words in the extant texts of Matthew and Luke as compared to Markan passages."

Goodarce summarized his objections on his web page "Ten Reasons to Question Q." He argued from silence (objections 1, 2, 4). He also heightened agreements between Matthew and Luke against Mark, both major (objection 5) and minor (objection 6), as well as in the Passion narrative (objection 7). He held that those who promote the Q source ignore Luke's rather great literary abilities to reshape Matthew's narratives for his own theological ends (objection 10), yet sees Luke's deference to Mark and Matthew in certain details ("phenomena of fatigue" in objection 8). He argued that the narrative flow in parts of the "Q" contradicted the thesis that it was an early "Sayings Gospel" paralleling the Gospel of Thomas (objection 3). Goodarce criticized his opponents for their slavish and lazy "follow the crowd" attitude with respect to prior "Q" research ("legacy of scissors-and-paste scholarship" in objection 9).

Let's ignore Goodarce's last objection as mere ad hominem. Let's also set aside his argument against the "Q" as a "Sayings Gospel" since similarities between it and the Gospel of Thomas teased the interests of most scholars; making a "hard and fast" case for "Q as Sayings Gospel" really wasn't necessary. Instead, let's consider both theories in light of dependence.

5. Matthew and Luke sans Mark: The Issue of Dependence

The Two Source and Farrer hypotheses differed primarily on the issue of dependence. While both agreed Matthew and Luke depended upon Mark, the former held both Matthew and Luke depended independently upon a hypothetical source. The later claimed Luke depended directly upon Matthew. Both camps consider the evidence and interpret in different ways.

a. Q and Mark Overlap?

In ten instances within Matthew and Luke, we find additional wording to verses shared with Mark; these represented a majority of the multi-word instances cited from the Wikipedia article above. Goodarce simply posited that Matthew expanded Mark's passages, then Luke inherited these expansions from Matthew; he point to them as problematic for scholars like Kloppenborg.

Defenders of the "Q" thesis call this additions the "Q-Mark overlap." They were:

| Theme | Mark | Matthew | Luke |

|---|---|---|---|

|

John's Preaching |

Mk 1:2-6 |

Mt 3:1-2, Mt 3:7-10, Mt 3:11-12 |

Lk 3:2, Lk 3:7-9 |

|

Jesus' Testing |

Mk 1:12-13 |

Mt 4:1-11 |

Lk 4:1-13 |

|

Beelzebul |

Mk 3:22-27 |

Mt 12:22-30 |

Lk 11:14-26 |

|

The Hidden Revealed |

Mk 4:24 |

Mt 10:26-27 |

Lk 12:2-3, Lk 12:4-7 |

|

The Mustard Seed |

Mk 4:30-32 |

Mt 13:31-32 |

Lk 13:18-19 |

|

Mission Instructions |

Mk 6:8-13 |

Mt 9:37-38 |

Lk 9:57-60 |

|

Sign Demanded |

Mk 8:11-12 |

Mt 12:38-42 |

Lk 11:16, Lk 11:29-32 |

|

Carrying One's Cross |

Mk 8:34-35 |

Mt 10:37-39 |

Lk 14:26-27 |

|

On Divorce |

Mk 10:11-12 |

Mt 5:32 |

Lk 16:18 |

|

On False Messiahs |

Mk 13:21-22 |

Lk 17:20-21 |

Kloppenborg denied any trouble with the overlap by differentiating between wording and theming. He pointed out that Matthew and Luke copied the wording of the passages closely, even word-for-word, but arranged them to emphasize different themes. Hence, he held that, if Luke did copy from Matthew, we would expect him to sharpen and improve the concerns of the prior author, not radically change them as was the case. If Matthew and Luke copied from a source independent of each other like (Mk and "Q") to (MT or Lk) proposed, such a problem disappeared (Kloppenborg, 31-34).

The disagreement came down to a dependence of source. In the Two Source theory, Matthew and Luke depended upon the hypothetical "Q" source; in the Farrer theory, Luke depended upon Matthew.

b. Relocated "Q" sayings.

As Kloppenborg noted above, Luke took various passages shared with Matthew and placed them into different contexts. They were:

| Matthew | Mt Context | Luke | Lk Context |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Mt 8:5-13 |

Centurion's Faith | Lk 13:28-29 | Narrow Door |

|

Mt 8:18-27 |

Boarding Boat | Lk 9:57-60 | On the Road |

|

Mt 10:7-42 |

Missionary Instructions | Lk 14:26-27 Lk 17:33 |

Saying Among Teachings |

|

Mt 11:20-23 |

After Comments on the Baptist |

Lk 10:13-15 | After Sending Out 72 |

|

Mt 12:31-37 |

Healing Demonic | Lk 12:10 | Acknowledge the Christ |

|

Mt 13:1-35 |

Among Other Parables | Lk 13:18-20 | Parable between Conflicts |

|

Mt 17:20 |

Healing of Demonic Boy | Lk 17:6 | Increase Our Faith |

|

Mt 18:6-22 |

Instructions to Disciples – Parables on Forgiveness | Lk 15:4-7 Lk 17:3-4 |

Parable Against Pharisees – Instructions to Disciples |

|

Mt 19:28 |

Rich Young Man | Lk 22:28-30 | Greatest at Lord's Supper |

|

Mt 21:33-22:14 |

Parables Against Leaders | Lk 14:16-24 | Parable Among Teachings |

|

Mt 23:1-39 |

After Condemning Leaders | Lk 13:34-35 | After Warning from Pharisees |

|

Mt 24:23-28 |

On the Mount of Olives | Lk 17:23-24 Lk 17:37 |

To Disciples Against Pharisees |

|

Mt 24:29-41 |

On the Mount of Olives | Lk 17:26-27 Lk 17:34-35 |

To Disciples Against Pharisees |

|

Mt 25:14-30 |

Parables on Final Days | Lk 19:12-26 | Towards Jerusalem |

Kloppenborg pointed to these shifts as evidence against the Farrer thesis where Luke depended upon Matthew. Goodarce countered that Luke depended upon Mark's sequence primarily, then edited Matthew accordingly to fit into his flow and thematic concerns.

The two camps touted the editing abilities of the individual evangelists. Those who defend the Two Source theory insisted Matthew was superior to Luke while those who held to Farrer proposed the opposite. Even if we ignored those judgments, we must still ask the question: why did Luke move those shared verses when Matthew's placement made perfect sense?

b. "Minor Agreements"

The majority of agreements between Matthew and Luke against Mark consist of one, two or three words. Many of single word consist of "and" ("kai" in Greek). Defenders like Kloppenborg wave away many of these instances as editing. Matthew and Luke improved Mark's inelegant Greek by streamlining the word flow and use of more appropriate phrases/constructions. In other words, Matthew and Luke seemed to have a better sense of good Greek (possibly as native speakers) than Mark did (as one possibly who spoke Greek as a second language).

Kloppenborg did recognize a problem with only four instances:

"fringe" in Matthew 9:20 and Luke 8:44 but not Mark 5:27.

"to know the mysteries of the Kingdom of heaven/God" in Matthew 13:11 and Luke 8:10, while "to you the mystery of the Kingdom of God is given" Mark 4:11.

"you faithless and perverse generation" in Matthew 17:17 and Luke 9:41, while "you faithless generation" in Mark 9:19.

"Prophesy! Who struck you?" in Matthew 26:68 and Luke 22:64, while "Prophesy!" in Mark 14:65.

Scholars have proposed many possible explanations for these and other discrepancies. Two stood out: interaction with oral traditions and scribal interference. If the "Q" document existed, it would not supersede the oral tradition it was based upon; more likely oral transmission continued and even acted as a corrective to Matthew and Luke. In addition, the generations of scribes who copied the gospels might have "corrected" the texts to their satisfaction. In other words, we cannot simply reduce the problem of "minor agreements" directly to the authorship of Matthew and Luke.

c. Argument from silence.

As I mentioned in the commentary on Second Corinthians, the argument from silence really depends upon probability and simplicity. Goodacrce rightfully broke his argument into three parts: the existence of the "Q" itself (probability in objection one), any mention of the "Q" in textual sources (probability in objection two) and the use of Occam's razor against the "Q" (simplicity in objection four). In other words, what's the probability that a document we call the "Q" source actually existed? And, does eliminating the hypothesis of the "Q" streamline scholarship on the Synoptics? As supporters of the "Q" point out, a vast majority of ancient writings have been lost; scholars estimate approximately only ten percent still exists. So, silence in the historical record does not preclude the existence of such an early Church document. Nor does it deny the tradition of oral transmission that, over the decades, gathered sayings and narratives into a form that allowed memorization.

Personally, I have a problem with scholars who treat the argument from silence as a certainty rather than a question of probability and simplicity. Such an argument can not stand on its own merits but requires other evidence to prop it up.

As I will argue below, eliminating the "Q" hypothesis does not simplify study of the Synoptics. In fact, it will complicate interpretation of Luke.

5. Luke Exclusive from Matthew

Before we conclude, we must consider the third aspect of studying the Synoptics: passages found in Luke that differed from Matthew's account. Here we find the genealogy of Jesus (Lk 3:23-28 vs. Mt 1:1-17), the Infancy Narrative (Lk 1:1-2:52 vs Mt 1:18-2:23) and the post-Resurrection scene (Lk 24:8 vs. Mt 28:11-20).

Goodarce argued that, in these cases, themes between Luke and Matthew overlapped, so he held Luke's dependence on Matthew was plausible. Take, for example, the Infancy Narratives. In his podcast "Conflicting Christmas Stories," Goodacre pointed to details Luke and Matthew shared in their respective narratives about the birth of Jesus to show dependency of Luke upon Matthew (virginal birth, announcement by an angel and so on). But such items could have easily come from oral tradition. And correlation did not prove causality; common themes did not mean dependence.

6. Conclusion.

No matter which theory we might find attractive, it remained a hypothesis, an abstract construct to explain the relationship between various pieces of evidence in order to create a believable narrative. As I mentioned at the beginning, we need to ask three questions about the evidence we find in the Synoptics. First, what materials did all three Synoptic gospels share? Second, what verses Matthew and Luke share that were not found in Mark? Third, what passages were exclusive to Matthew and Luke individually? The most attractive hypothesis explained the relationships between those three questions in the simplest narrative possible with the least amount of problems.

The straight line theory adequately answered question one, barely answered question three but failed on question two. Neither Mt-Mk-Lk nor Lk-Mk-Mt could explain the verses shared between Matthew and Luke. The Greisbach hypothesis, (Mt to Lk) to Mk, could not answer why Mark rejected both the shared and exclusive materials found only in Matthew and Luke (questions two and three). The Farrer theory, (Mk to Mt) to Lk, overcame the weakness in Greisbach's by replacing Matthew with Mark, thus giving the shortest gospel priority (question one). However, as a conflation theory, it made weak arguments about the shared verses between Matthew and Luke (question two) and attempted to gloss over the exclusive passages of Matthew and Luke (question three).

Goodarce also complicated the task of interpretation. Using a few tools to describe Luke's dependence on Matthew, he did not explain why Luke wrote his gospel in the way he did. Why did the evangelist decide to copy at one point, treating Matthew as a superior source, then scarcely consider him in creating his passages and treating him as an inferior source? To answer that question, we need to consider Luke passage by passage and, in some cases, word for word. Thus, Goodarce tried to cover too much ground with too few resources.

The Two Source theory eliminated most of this problem by minimizing Luke's dependence to a set of narratives and sayings that Matthew also shared. In addition, it allowed for the evangelist to create exclusive narratives apart from Matthew. In other words, by positing a hypothetical source independent of Matthew and Luke, the proponents of the Two Source theory shrank the problems scholars like Goodarce faced.

The Two Source hypothesis was actually a better candidate to claim Occam's razor for it clarified what the Farrer theory muddled. (Mk and Q) to (Mt or Lk) simplified study of the Synoptics by ultimately appealing to a source that found its roots in oral traditions. Indeed, based upon the use of form criticism, a real strength of the "Q" thesis lay in the possibility that scholars could peer into the oral tradition.

In another section of this web site, I offer a commentary on the "Q" source and consider how these verses could have been used by the early Church.

B. From Oral to Written Tradition

1. The Oral Tradition

By its nature, oral tradition in the early Church hid in the fog of history. For over two decades, the early Church produced no written materials about the content of the faith. However, Paul's letters take a snapshot of the communities in the mid 50's CE, when the Christian oral tradition thrived. In addition, later writings (especially the gospels and Acts) give us a good indication of the Church's self-image. With these two sources, we can make a few educated speculations how oral tradition developed.

From these documents, we can glean two interweaving qualities: the urgency of the gospel message and the immediacy of the spiritual experience. Early missionaries saw themselves carrying on the mobile ministry of Jesus; the effect of those efforts resulted in charismatic phenomena. As Paul himself stated:

My speech and my preaching were not in persuasive words of human wisdom, but in demonstration of the Spirit and of power, that your faith wouldn't stand in the wisdom of men, but in the power of God.

1 Corinthians 2:4-5

While urgency and immediacy interlock, let's consider them individually to get a flavor for the oral culture of the early Church.

a. Urgency of the Message

Paul Preaching

in Athens

by Raphael

The Good News possessed an internal urgency to spread upon its apocalyptic content and its mobile delivery. The faithful fervently held to the immanent return of the Christ. In 1 Thes 4:13-5:10, St. Paul taught the Second Coming that he expected to come suddenly and unexpectedly. That belief focused the Church primarily on the task of evangelization, secondarily on community living.

Early Christian literature depicted the ministry of Jesus and the missionary activities of the early Church as mobile. Instead of a pilgrimage movement where the populace traveled to see an enlightened guru, the thrust of the outreach brought the Good News to the people where they lived. Missionaries proclaimed (kerygma) the Good News (evangelion) to the uninformed. The gospels emphasized the importance of the messenger, likening him to the town crier proclaiming official information. Quoting Mal 3:1 and Isa 40:3, the Synoptics described the Baptist as "a voice of one crying out in the wilderness" (Mt 3:3, Mk 1:2-3, Lk 3:4-5). In Acts 2:1-12, the Spirit-filled disciples proclaimed the message in a way that even foreign pilgrims could understand; in Acts 2:14-36, Peter preached the Good News to crowds gathered for Pentecost. These cases reflected the overall tone of kerygma, proclamation; the preacher proclaimed the gospel in order to affect metanoia, moral conversion as a step to faith. "Repent and believe in the Good News!" (Mk 1:15)

But those who delivered the message did not travel alone. Except for the stories of Philip (Acts 8:4-8, Acts 8:26-40) and Apollos (Acts 18:24-27), passages about evangelization detailed groups spreading the gospel. Jesus called his disciples to followed him (Mt 10:1-4, Mk 3:13-19, Lk 6:12-16). Paul traveled at first with Barnabas (Acts 13) then with an entourage (Acts 15:40-16:6). Thus, the spread of the Christian message depended upon the preachers (as a group) reaching out to the people. Jesus' instructions to his advance parties (Mt 10:5-15, Mk 3:13-19, Lk 9:1-6) presented the paradigm: travel at least in pairs to visit new territories.

b. The Immediacy of the Spirit in the End Times

Not only did believers expect the immanent Second Coming, they found convincing evidence that they lived in the midst of the end times. Referring back to Acts 2:17-21, Peter quoted Joel 2:28-32 as proof that the work of the Spirit (in this case, the glossolalia that the Pentecost crowd witnessed) pointed towards the presence of the eschaton. Early Christian missionaries appealed to the dire conditions of society as a counter-point to a message of hope and demonstration of spiritual power.

In Rom 12:6-8 and 1 Cor 12:8-10, Paul listed spiritual gifts or charisms found in the early Christian communities. He saw these gifts as freely given by the Spirit and not due to the talents or efforts of individual believers. He inferred these charisms existed for the good of the community itself, giving it the means to thrive even in the presence of persecution. In other words, the Church was the Spirit-infused assembly of the saved that lived in a corrupt world rushing towards the destruction from God's wrath.

c. Corollaries to Urgency and Immediacy

Urgency of spreading the Good News and the immediacy of spiritual experience resulted in a tension between the accuracy of the message and its expansion. Group missionary efforts acted as a corrective to the preacher's message. If someone deviated from the narrative agreed upon by others, they would inform him of his error. In Acts 18:26, Priscilla and Aquila "explained to (the missionary Apollo) the way of God more accurately." Thus, the community organically produced a feedback loop to more or less correct deviations made by individuals.

Recent work on communal memory supports this insight. People collectively remember events far more accurately than as individuals simply because they can contribute widely differing experiences and insights. Individuals also defer to group remembrance, even to the extent they don't put in the effort to remember and deflect responsibility away from themselves. To combat this lax attitude, the group might develop a official record as a memory touchstone (like group minutes).

Group missionary work thus insured increased accuracy of the message based upon the inclination of the individual to defer to the group, the corrective feedback loop created and the efforts to develop a memory touchstone. These factors might help to explain why some "Q" verses in Matthew and Luke track word-for-word; it also might help to explain the same phenomena between the Synoptic and Johannine traditions in the Passion narrative. Early Christians prized the message and tried to pass it along as accurately as they could.

Despite the drive to preserve the Good News, the evangelistic urgency and spiritual immediacy drove a thirst for believers to know more about Christ and his Good News. There were, not one, but two sources: 1) the words of and narratives about the historical Jesus and 2) prophetic announcements in the name of the Lord. Believers naturally wanted to know more about the sayings and stories of Jesus. Fulfilling such a desire could explain the Mark-Q overlap.

The charismatic-prophetic environment of the early Church communities also contributed to pool of sayings. The phrase "Thus says YHWH" occurred over 400 times in the Hebrew Scriptures to denote the divine will, especially in the prophets. In the New Testament, Christians also sought the will of Jesus through prophecy. In the book of Revelation, John the Divine recorded the words of Jesus based upon his visions (Rev 1:11, Rev 1:17-20, Rev 22:12-17). Paul himself implied a differentiation between his personal advice (1 Cor 7:10, 1 Cor 7:12) and the will of Jesus (1 Cor 16:7). In Acts 20:21, he even quoted Jesus with a saying not recorded in the gospels: "It is better to give than it is to receive." (Was this an actual quote from the Nazarene or a prophetic utterance that made its way through the community?) In a charismatic, apocalyptic community like that of the early Church, prophetic utterances carried weight. Missionaries would pass along those that rang true with the greater Christian message, possibly adding these sayings to the oral canon. Thus, traditions about the Nazarene could grow.

d. Conclusion about the Oral Tradition

We who read Scripture might assume early Christians shared our outlook on the Good News. Our view depends upon the literary authority of the New Testament and, before the advent of the books, the leadership of the Apostles. For clarity, we lean on a picture of unity, an agreement of texts and a clear apostolic tradition. Scholarship, however presented a far messier reality.

Christian missionaries delivered the Good News to uncharted territories. They established small communities from which new believers would share the faith with family and friends by word-of-mouth. By the mid-first century CE, the Church consisted of a few thousand believers spread across the eastern Mediterranean basin, even to Rome itself. These communities contained an energy based upon the urgency of the apocalyptic message and the immediacy of a charismatic environment that emphasized prophetic visions/utterances. The priority of missionary work gave believers little time or need for writing down stories about Jesus, since these faithful depended upon the first or second hand oral accounts of those who knew the historical Jesus (the apostles) or those who felt personally called by the Risen Lord (Paul). And as believers grew in number, they transmitted the faith orally as accurately as they could and sought to add to that pool of information.

2. Factors for Writing the Gospels

a. Transition from the Oral Culture

Mark penned

his Gospel

by Borovikovsky

The transition from the oral to the written culture of the Church had literary roots. Christianity grew out of Judaism, a religion of the Book. Unlike any other worship traditions in the ancient world, Judaism based its practices on a written Law; around that collection of divine edicts, it gathered prophetic and wisdom traditions, prayers and hymns, even histories into a literary work we call the Hebrew Scriptures. Early Christian missionaries preached from the Septuagint, a Greek translation of that collection, hence adopting Judaism's literary culture as its own.

Jews promoted their Scripture at weekly meetings in the local synagogue. These gathering consisted of prayer (blessings to God and a recitation of Deu 6:4), readings from "the Law and the Prophets" (Hebrew Scripture) and a commentary, sometimes given by a visitor. The gospels alluded to Jesus teaching in various synagogues (Mt 4:23, Mk 1:29, Lk 4:14-15, Jn 18:20). The ceremony would end with the Aaronic blessing over the people (Num 6:24-26). But, unlike the formal ceremonies we find in synagogue and church services of today, ancient synagogue services could have an informal flavor, leading to dialogue and discussion, either during or after the service. Consider Luke's narrative about Jesus teaching in the synagogue and the reaction of the crowd at Nazareth (Lk 4:14-27).

Early Jewish Christians would attend synagogue services along with their non-Messianic brethren (see Acts 13:14-43). But, by the time John wrote his gospel in the 90's CE, he noted believers were barred from gatherings (Jn 9:29). So, Christians adopted and adapted the service for their own needs with prayer, readings from the Hebrew Scriptures and commentary. Along with the Scriptural passages, letters from Church leaders were read to the congregation (Col 4:16, 1 Thes 5:27, Rev 22:18). Thus, churches began to give these letters and prophecies the same weight as "the Law and the Prophets."

As congregations gave these proclaimed Church documents authority, they quickly developed a scribal infrastructure to copy and disseminate them. In the non-canonical "First Letter of Clement" (written circa 95 CE), the author addressed the Corinthian community from his leadership role in Rome. He alluded to a shared familiarity with Paul's letters, the letter to the Hebrews and possibly parts of Acts, James and 1 Peter. Such a reference could not be possible without local Christian scribes.

So, when the evangelists put pen to paper, they fed their works into that literary culture. Scribes quickly copied their gospels and shared the works with other communities, giving early churches a way share the Good News with their members. The oral tradition faded away by the early second century and the read gospels replaced spoken witness as the primary means of proclamation.

b. Crises That Led to the Written Culture

We might assume that, once the evangelists put pen to paper, the age of the oral tradition ended and the primacy of the written gospel took root. Again, scholarship argued against any such outlook. Author Luke Timothy Johnson saw the forty years between the death of Jesus and the fall of Jerusalem as a tumultuous period where the Jesus movement underwent five major shifts: 1) geographic from Jerusalem into the Diaspora, 2) sociological from the rural, mobile ministry to a movement found in urban homes, 3) linguistic from Aramaic to Koine Greek, 4) culturally from Judaism to Greco-Roman and 5) demographically from Jewish-Christian to majority Gentile Christian. In other words, the Jesus movement was no longer just a small Jewish sect but was quickly evolving into the distinct Gentile religion we know today.

Within this radical shift, Johnson proposed four converging reasons why the evangelists found it necessary to compose the written documents we call "gospels."

1) Death of Eye Witnesses

The evangelists composed their works within an oral culture, but one they realized was slowly dying. By the 70's CE, pagans had martyred the Apostles; death had claimed other primary witnesses to the historical Jesus. The general culture and the Imperial court itself turned against the faith. Those who encountered Peter, Paul, Apollos and the other missionaries younger in life now grew gray with age. Soon their voices would be silenced.

2) The Loss of the Mother Church at Jerusalem

According to the Church historian Eusebius (260-340 CE), believers withdrew from Jerusalem during the Great Jewish War and settled in a town of the Decapolis called Pella. Christians throughout the Empire lost felt connection to Palestine. The mother community disappeared, leaving other communities a sense of loss. The faithful could no longer appeal to the leadership in the city as a final authority to adjudicate controversies and insure the accuracy of the message.

3) Growing Distance between Jews and Christians

After the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, Judaism slowly began to reorganize itself, depending upon the leadership of the Pharisees. Tensions between Jewish-Christians and those Jews who rejected the Jesus message intensified. By the end of the first century CE, both camps had developed separate communities and infrastructure, replacing dialogue with apologetics and ad hominem attacks. While Luke and Matthew placed that battle in Palestine, they used that geography to reveal religious scraps on the local levels of their readers.

4) Growing Gentile Majority in the Church

The influx of Gentiles into the Church only exasperated the conflict mentioned above, but it also radically changed both the make-up and the outlook of the Christian communities. Gentile Christians partook in a Greco-Roman culture, so they naturally interpreted their adopted Jewish roots (Hebrew Scriptures and traditions) through that lens and emulated what they admired in that culture (Koine literature, even philosophy).

In other words, the Church could not sustain the oral tradition. Communities slowly lost eye witnesses and felt adrift with the mother Church in Jerusalem gone. With the rising Gentile majority, the movement shifted in language, location and cultural outlook. And the counter-cultural nature of the faith garnered opposition from pagan and Jewish quarters alike. The Church needed a new touchstone for the basis of Christianity, since it felt the old one slipping away.

C. Dating the Synoptics

Synoptics Dating Links

Since the Church could not sustain an oral culture for vitality and growth, it needed a written one, specifically a collection of sayings and narratives about the Jesus it worshiped. According to the Two Source hypothesis, the gospel of Mark first filled the void with Matthew and Luke to follow. But, when did the evangelist write it? Here, we must consider various factors both within the gospel and outside it to determine a date.

Some Two Source scholars argue that Mark wrote his gospel in the 50's CE (early date thesis) based upon three issues:

1) Luke depended upon Mark as a source.

2) Luke wrote before the early 60's

a) since Acts was connected to the gospel of Luke based upon a common authorship and themes

b) and since the ending of Acts did not contain known historical events that occurred from the mid-60's to the mid-70's CE (the martyrdom of Peter and Paul, Nero's persecution of Christians in Rome, the Great Jewish War and the destruction of Jerusalem).

3) The historical Jesus did predict the destruction of the Temple with the fall of Jerusalem (Mk 13:1-2).

Those who propose a date of 70 CE downplay the lack of historical details at the end of Acts (argument 2b) and insist that Mark put the prophecy about the destruction of the Temple into the mouth of Jesus after the fact (argument 3). Let's consider argument 3 below but wait about argument 2b when we investigate the dating of Luke-Acts.

1. Dating Mark: early 70's CE

a. External factors

Symbol for

Mark the Evangelist

As the decades of the first century CE rolled on, pressure on the Church, both pagan and Jewish, increased. Paul's undisputed letters only mentioned conflict with other Jews (both Christians and non-Christian) over his controversial views on Gentile admission into the Church. But as the 50's became the 60's CE, pagan culture (especially the Imperial court) became aware of the growing Jesus movement and considered it anti-social, even atheistic since it did not recognize the pagan gods and their festivals. Facing officially sanctioned prejudice and, in some cases, persecution, believers felt the temptation to waver in their commitment.

Mark's gospel addressed that issue head on. It presented the disciples as clueless followers who regularly failed to understand Jesus and his mission (Mk 4:13-14, Mk 4:40-41, Mk 5:30-31, Mk 6:35-37, Mk 6:51-52, Mk 7:17-18, Mk 8:14-21, Mk 8:31-33, Mk 9:5-6, Mk 9:9-10, Mk 9:30-32, Mk 10:35-40). Even when followers had insight at the Passion, they cowered in their commitment. Despite Peter's declaration of commitment (Mk 14:30), Peter denied Jesus three times (Mk 14:30, Mk 14:66-72). Peter, James and John slacked in their watchfulness at Gethsemane (Mk 14:32-42). All the disciples abandoned Jesus at his arrest (Mk 14:50-52). Even when the women heard the young man proclaim the Good News of the Resurrection, they fled, hid and said nothing out of fear (Mk 16:6-8). Thus, Mark ended his gospel with implicit questions to his audience: Do you really know what discipleship really means? In the face of opposition, even persecution, will you cave to pressure? Or will you proclaim the Good News despite the costs?

These disturbing questions had a better fit with the hardening public attitudes against Christians in the late 60's CE onward. Paul's undisputed letters of the mid to late 50's CE did not reflect these prejudices.

b. Internal factors

Now it's time to consider Mark 13:1-2:

1 As HE departed from the Temple, one of his disciples said to him, "Teacher, look at the (great) manner of stones and buildings!" 2 JESUS said to them, "Do you see these great buildings? A stone will not lay atop (another) stone which will not be demolished."

Did Jesus really predict the destruction of the Temple? Or did Mark place that prophecy in the mouth of the Nazarene after the fact? More "conservative" commentators answer "yes" to the former question, thus arguing for an earlier date of the late 40's to the mid 50's CE. Those "liberal" scholars who find truth in later question argue for the early 70's CE, after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem.

Which camp is right? For argument's sake, let's grant that Jesus actually pronounced the Temple's demise during his lifetime. However, by focusing merely on the Mk 13:1-2, many scholars missed the import of the disciples' response:

3 As HE sat on the Mount of Olives directly opposite the Temple, Peter, James, John and Andrew asked HIM in private, 4 "Tell us when these things will be and what sign is about to fulfill all these (events)?"

His followers interpreted Jesus' prophecy as an eschatological declaration. He defined the destruction of the Temple as an end times event. Indeed, chapter 13 (also known as the Little Apocalypse) concluded with the Son of Man's return (Mk 13:26-27). In between these events, national even cosmic catastrophes would occur, interspersed with personal rejection by family and co-religionists, desecration of the Temple area itself and the siren call of false Messiahs.

Chapter Thirteen described the end times beginning with destruction of the Lord's house, the place where the faithful believed YHWH lived, and ending with the true dwelling place of God's presence, the Son of Man, appearing in glory. Does this sound familiar? It should:

Standing up, some offered false testimony against HIM, saying, "We heard HIM saying, ‘I will destroy this hand-built Temple and build another not made by hands in three days.'" Mark 14:57-58

Mark echoed the eschatological theme of Temple destruction and returning divine presence, this time in the mouth of the Jesus' enemies. This statement found a similar place in Mt 26:61 and Jn 2:19. The differences between three verses primarily lie in the agency of the Temple destroyer and the vessel of returning presence. In Mk 14:58 and Mt 26:61, the false witnesses accused Jesus of being the agent and believed divine restoration meant a rebuilt edifice. In Mk 13:2, Jesus expressed agency in the passive, thus not identifying the actor; he predicted the return of divine presence in the Second Coming (Mk 13:26-27). In Jn 2:19, right after the cleansing of the Temple, Jesus shifted agency to the leaders with the imperative "Destroy this temple..." He also shifted the focus of divine presence away from the Temple to himself, thus framing the return of presence as the Resurrection (Jn 2:21). Notice his opponents, just like the false witnesses at the Caiaphas trial, held Jesus referred to the physical Temple on Mount Zion (Jn 2:20).

So, did Jesus actually predict the destruction of the Temple? Many scholars answer "yes" when they invoke the criteria of embarrassment, the notion that, if the gospels recorded something Jesus did or said that embarrassed early Christians, it probably did go back to the historical Jesus. The prophecy also had multiple attestations. According to these scholars, Jesus prophesied the destruction of the Temple as an eschatological event. The house of the Lord would crumble and be replaced by God himself. Taken at face value prior to 70 CE, many Jews, including Jewish Christians, could have found such a statement abhorrent, considering their devotion to the Temple. Other early Christian could have interpreted the statement in allegorical terms, just as Jn 2:19-21 did. Enemies of the Nazarene could shift the saying into heresy with the simple change of a pronoun and verb tense from the passive ("the walls will fall…") to the active tense, third person ("he will destroy the Temple"). In other words, Jesus' eschatological prophecy about the Temple caused consternation among early believers and gave enemies apologetic ammunition. It proved to be an embarrassment to the Church.

That belief held until 70 CE when the Romans breached the walls of Jerusalem and torched the Temple. Then, Christians could point to the ruins as a sign that the end was near, for with they witnessed Roman civil wars in the Year of the Four Emperors (69 CE) and experienced tremors common in the Mediterranean basin (Mk 13:7-8). By the late 60's CE, they encountered prejudice and persecution from Pharisaical Jews and pagans alike, even on a personal level (Mk 13:9-13). They knew that, at the sight of the Roman standard ("'the abomination that causes desolation' standing where it did not belong"; see Dan 9:27, Dn 11:31, Dn 12:11), the faithful had abandoned the holy city to Pella (Mk 13:14-19). They felt their communities torn apart by the allurements of greedy missionaries and false teachers (Mk 13:21-22). They awaited the ultimate cosmic signs of eclipses and meteor showers to reveal God's wrath (Mk 13:24-25, see Isa 13:10, Isa 34:4). In other words, early Christians believed they were living in the midst of the end times. With the fall of the Temple in 70 CE, Mark no longer felt embarrassed acknowledging Jesus' prediction. It was being fulfilled in the evangelist's midst.

c. Factor of Tradition

Peter dictated Gospel

to Mark

by Ottini

Let's turn the topic from dating to place, not "when did Mark write his gospel?" but "where did he write it?" Second century CE leaders like Papias of Hierapolis (60-163 CE), Clement of Alexandria (150-215 CE), Irenaeus (130-202 CE) and Justin Martyr (100-165 CE) connected Mark to the Petrine community in Rome, implicitly based upon 1 Pet 5:13 (Babylon signified the Imperial capital). Many scholars support this thesis based upon the Latin terms in the text ("census" in Mk 12:14; "fregelloun" in Mk 15:15). They also point to Aramaic terms (possibly from the apostle himself) that the text translated for the audience (Mk 3:17, Mk 5:41, Mk 7:34, Mk 14:36, Mk 15:34). However, some scholars argue against the "Mark from Peter" thesis. They hold the evangelist did not have a good knowledge of Palestinian geography, confusing the placement of towns (switching Bethany and Bethphage on the Jericho road to Jerusalem in Mk 11:1) and local areas (Jesus' travel to the northern Tyrian territory via Sidon and south beyond the Sea of Galilee to the Decapolis in Mk 7:31). They also contend Mark employed narratives from oral traditions in circulation at the time, independent of a Petrine source. Nevertheless, if Mark wrote his gospel after the death of Peter in Rome (see Irenaeus "Against the Heresies" 3.1.1), he reasonably put pen to paper in the same time frame suggested. According to tradition, Peter died in the mid-60's CE, concurrent with Nero's local persecution (and in agreement with the "external factors" above).

Thus, the social situation the Christians found themselves in, the prophecy Temple destruction and return of the divine presence, even the second century tradition of authorship based in the Petrine community at Rome, all argue for authorship in the early 70's CE.

2. Dating Luke-Acts: mid-80's CE

more likely 90's CE

Symbol for

Luke the Evangelist

As stated above, one of the major objections to a late dating of the Synoptics lie in Act's lack of historical reporting towards the end of the Apostolic Era. It did not record the death of Peter and Paul, Nero's persecution of Christians in Rome or the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. Hence, some scholars date the documents in the early 60's CE just after Paul's arrival to Rome. This view, however, missed the greater picture. It does not address the question of dating in light of why Luke wrote Acts.

a. Why was the book of Acts written?

Many have described Acts as the "early history of the Church." They assume the text merely related the events of Peter's, then Paul's ministry. But, such assumptions miss the larger picture.

We must recognize the book of Acts was the second part of a work many scholars call "Luke-Acts." Based upon common language, writing style and theology, almost all scholars recognize the same author wrote the gospel of Luke and the book of Acts.

Next, we must tease out the reasons the author we call "Luke" penned his two part work. According to Luke 1:4, the author wrote to assure the reader that the content of the faith was reliable. But, as the commentary of the Infancy Narrative and Acts showed, the faith relied on the activity of the Spirit. The power of God drove the people and the events found in Luke-Acts. Hence, the Spirit was the primary actor, especially in Acts.

In addition, we must discover the historical viewpoint of Luke. He did not see history as a sequential flow of facts and dates, like we do. Instead, he wrote in a culture that recorded events for moral reasons (so the mistakes of the past would not be repeated) or as propaganda for the emperor; that culture also assumed history was composed of eras that ebbed and flowed endlessly. Instead, he held a counter-cultural view that history would finally end with the Second Coming. So, he penned Acts through the lens of Christian faith; he arranged all the people and events in the "early history of the Church" moving toward that end point.

Finally, Luke wrote his work to help Christians of his era answer questions about their place in the world. They gathered and believed base upon divine initiative, not of their own accord; as a result, they faced rejection, isolation and prejudice. If the author wrote the first part of Luke-Acts to flesh out the object of their devotion (Jesus the Christ), he composed the second part to explain why they lived as they did (Spirit-infused). He also reminded his audience that, no matter what obstacles they faced, no opposition could stop the work of the Spirit. Ultimately, this was the real reason Luke wrote Acts. And, this gave his audience hope.

Does this mean Acts wasn't historically accurate? No. A modern analogy is helpful here. Non-fiction novels have grown in popularity recently; these books contain historical details in a popular genre. More importantly, these works help to explain the present condition through the lens of past events. Clearly, these books differ greatly from a history text; they tell history in an entertaining and meaningful way. The book of Acts was more like a non-fiction novel than a history text book. It not only told what happened, but why it happened.

b. What was an appropriate ending for Acts?

Those who view Acts as a mere history of the early Church face two vexing issues. First, the abrupt end of Acts did not address the historic events of the late Apostolic era or the shift in Church life from missionary efforts to community maintenance. Second, the beginning of Luke and Acts contained eloquent appeals to "Theophilus," yet did not sum up the works with a conclusion of faith to the recipient. Instead, Acts 28:31 ended the book with Paul living under house arrest, welcoming all visitors, "proclaiming the Kingdom of God, freely teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with a total confidence." Acts lacked closure.

But, the reasoning above contains a flaw. It finds the ending of Acts deeply dissatisfying because those final verses do not answer the question: what's next? We know what happened. Why doesn't Luke record it? But the author did not compose the work as a "blow-by-blow" account of the early Church. He wrote it to portray the Church as a Spirit-driven phenomena that would overcome any opposition.

Think of Acts as a series of vignettes formed into a sequential narrative. Four themes drove each vignette:

1) Movement of the Spirit.

2) Proclamation of the Good News

3) Acceptance by some.

4) Rejection and opposition by others.

These four present several problems to the "Acts as early Church history textbook" view. First, any additional recordings of historical events would need to be couched in terms of those themes. And if they were included, how could they act as an ending to Acts?

Next, the proclamation of the Word dominated Acts. The text contained nineteen different sermons, eleven by Paul, five by Peter and one each by Stephen, Philip and James. An appropriate ending would consist with of a sermon that dovetailed with the beginning of the Spirit's activity in the Church. Compare the beginning of the Church's ministry at Pentecost scene with Act's final scene, using the four themes above. At Pentecost, Peter preached based upon the descent of the Spirit (Acts 2:1-11); Paul's preaching implied the movement of the Spirit. Peter proclaimed the Good News to Diaspora Jews gathered for the feast of Pentecost (Acts 2:5-11, Acts 2:14-36); Paul preached to the synagogue leadership in Rome consisted of Diaspora Jews from all parts of the Empire (Acts 28:17-22). At Pentecost, some compared the glossolalia of the disciples as drunkenness (Acts 2:13) while a large part of the crowd converted (Acts 2:37-41); at Rome, some became followers while others rejected the message (Acts 28:24).

Besides sharing the four themes, one similarity and one difference stood out. Both Peter and Paul proclaimed the message to a cosmopolitan, Diaspora audience. However, unlike Peter, Paul turned his evangelistic efforts towards the Gentiles (see Acts 9:15, Acts 13:46-48; Acts 28:25-28). The Diaspora audience and the ministry among the Gentiles spoke to the universal nature of the Good News. God invited everyone into the Kingdom through faith in Christ. This message resonated with Luke's majority Gentile audience.

Finally, Acts 28:31 even summed up the book in miniature, capping it off with a message of hope. Paul, representing every missionary, continued "proclaiming (kerygma) the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ boldly and freely." The death of the apostles, persecutions like that of Nero or the destruction of the Temple would not stop the work of the Spirit, inflaming believers to always share the Good News.

So, Luke wrote an appropriate ending for Acts. He recapitulated the four themes of his Spirit-driven narrative, emphasized the universal nature of evangelization and gave his audience hope as they continued the ministry symbolized by Paul's efforts. These factors overshadowed the martyrdom of the apostles, Nero's persecution or the destruction of the Temple. Hence, the historical events that brought the apostolic era to a close do not carry the weight many scholars give them and, thus, do not impede one from holding a later date of composition for Acts (early 80's to 110 CE).

c. Conclusion

Several factors contribute to the dating of Luke-Acts. First, the themes found in Luke-Acts reflected an era in the Church's life where a majority Gentile membership fought a polemic battle with Pharisaical Jews, while keeping an open door to converts in a potentially pagan culture. This environment matched the conditions found in the early to mid post-Apostolic era.

Second, we have seen that Mark penned his gospel in the early 70's CE and Luke had a copy of his text, considering how close Luke copied Mark and kept the sequence of his verses intact. (We've also noted the lack of recording historical events in Acts did not stop Luke from writing his works after 70 CE).

Finally, scholars reasonably estimate the time scribes needed to copy and disseminate Mark's gospel took about a decade.

So, the earliest possible date for the evangelist to write Luke-Acts was the early 80's CE. A later date of 90's CE was more likely.

3. Dating Matthew: early to mid 80's CE

Symbol for

Matthew the Evangelist

The majority of scholars accept Matthew as a gospel originally written in Koine Greek for Jewish-Christian audience. Unlike Mark and Luke who appealed to the Gentiles, Matthew never explained Jewish customs, cited the fulfillment of the Hebrew Scriptures 68 times, began with a genealogy for Jesus as "son of Abraham, son of David" and contained five major discourses from the Nazorene (chapters 5-7, chapter 10, chapter 13, chapter 18, chapters 23-25) that paralleled the five books of the Jewish Law. The gospel assumed its audience would relate to a certain form of Judaism as followers of the Christ.

The Jewish character of Matthew's gospel led a minority of scholars to promote a Hebrew (or Aramaic) version that preceded the Greek version. They base their thesis upon the witness of the Church fathers beginning in the second century CE and upon attempts to reconstruct a Hebrew gospel from Matthew. Irenaeus (120-200 CE), Origen (184-253 CE) and the Church historian Eusebius (263-339 CE) held the evangelist either wrote a Hebrew gospel later translated into Greek or two versions, a Hebrew and a Greek. Some have attempted to translate the gospel into Hebrew, most notably the Shem Tov Matthew, a thirteenth century translation and polemic commentary by the Jewish rabbi, Shem-Tob ben Isaac Shaprut of Tudela. Most modern scholars reject the Hebrew Matthew thesis based upon a lack of textual evidence and see any reconstruction of a "proto-gospel" as a failed project simply because it depended upon the Greek text. Hence, few argued an "early date" thesis for Matthew based upon external factors of tradition or hypothetical reconstructions.

Some scholars argue for a pre-70 CE date based upon internal evidence found in Matthew, pointing to an existing Temple: paying the Temple tax (Mt 17:24-27), swearing by the Temple (Mt 23:16-22) and leaving the gift at its altar (Mt 5:23-34). Unfortunately, they failed to distinguish between the edifice of the Temple that the Romans destroyed in 70 CE and desire for temple cult which continued after the loss of the holy site. Jewish hopes rose with Hadrian's promise to rebuild the holy city with its Temple, only to have those hopes dashed with the erection of Aelia Capitolina in 130 CE; six years later, a Jewish rebel and aspiring Messiah nicknamed "Bar Kokhba" led a uprising against the Romans with the implicit aim of rebuilding the Temple. Priestly families survived and thrived after the Temple's demise, even receiving tithes and offerings (see Josephus, Antiquities 4.68). So, the Temple tax could refer to maintenance of the Levitical priesthood after 70 CE; swearing on the Temple and leaving one's gift on the altar could simply be allegory by Jewish Christians, referring to a future, idealized Temple.

Arguments for a later date parallel those of Luke: the primacy of Mark's authorship and the deteriorating relationship between Christians and Jews. And, like Luke, Matthew had a far more developed theology than that of Mark. However, Matthew lacked a sense of outrage and loss we assume he would have if he wrote the book after the destruction of the Temple. Contra that argument, many scholars hold the evangelist wrote his gospel with enough distance both temporally (10-15 years later) and geographically (in Antioch, some 600 miles north of Jerusalem) for his passions to cool.

So, the process reasonably took a decade for scribes to copy and disseminate Mark so Matthew, like Luke, could compose from the shorter gospel. Thus, the earliest date for Matthew to write his gospel was the early to mid 80's CE.

D. Conclusion

We've traveled far in our quest to date the Synoptic gospels. The relationship between Matthew, Mark and Luke was best described by the Two Source theory that placed Mark first and posited a hypothetical source called the "Q." An oral culture defined the period between the death of Jesus and the publication of the first gospel; traditions existed that resisted a written gospel and led to it's realization at the beginning of the post-Apostolic era. Both internal and external factors give us clues to the time frame of the Synoptics' publication and dissemination. In the end, we determined that Mark penned his short gospel shortly after the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. Allowing for copying and distributing of Mark by scribes, Luke and Matthew copied it when they constructed their gospels, as early as a decade later.

E. Sources

Kloppenborg, John S. Q the Earliest Gospel. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2008. Print.

Barnett, Tim. "Textual Variants: It's the Nature, Not the Number, That Matters | Stand to Reason." Stand to Reason. Web. 14 Jul 2018. <http://www.str.org/articles/textual-variants-it%E2%80%99s-the-nature-not-the-number-that-matters#.W0pub3Yzqqk>.

"New Testament apocrypha – Wikipedia." Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Web. 14 Jul 2018. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Testament_apocrypha>.

"Biblical manuscript - Wikipedia." Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Web. 16 Jul 2018. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biblical_manuscript>.

Johnson, Luke Timothy. Early Christianity: Experience of the Divine. Chantilly, VA: The Great Courses, 2002. Print.

Johnson, Luke Timothy. "Jesus and the Gospels," Lecture Eight. The Great Courses, The Teaching Company, Chantilly, VA. Audio. 2002.

Bratcher, Robert G. A Translators Guide to the Gospel of Mark. United Bible Societies, 1981.

Reiling, J., and J. L. Swellengrebel. A Handbook on the Gospel of Luke. United Bible Societies, 1993.

Newman, Barclay Moon, and Philip C. Stine. A Handbook on the Gospel of Matthew. United Bible Societies, 1992.

Photo Attributions

Two Source Hypothesis. Alecmconroy [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

Paul Preaching in Athens. Raphael [Public domain]

Mark Writing his Gospel. Vladimir Borovikovsky [Public domain]

Peter dictating to Mark. Ottini [Public domain]