Context

II. Greco-Roman Cultural Context

Overview

What was the world like when Christianity first appeared? To truly understand the books of the New Testament, we must investigate the culture in which they arose. To accomplish that task, we'll delve into the common characteristics of the Mediterranean cultures, briefly describe the history that gave birth to Greco-Roman, review the Empire's geography, infrastructure and urban life, look into its religious and intellectual life, then place Christianity into that context.

Overview Outline

A. Overview of Ancient Mediterranean Cultures

B. A Brief History of Greco-Roman culture.

1. Classical Greek Culture as Urban.

2. Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) and Hellenism.

3. Rome's expansion into the eastern Mediterranean.

4. Augustus and Greco-Roman culture.

5. Brief History of the Empire during the First Century after Augustus.

C. Empire's Geography and Infrastructure.

D. Urban Life in the Empire: the Polis.

1. Structures in the Polis.

2. Spread of the polis.

3. Other major Greek cities in the first century CE.

E. Religion and Philosophy in the Empire

1. Religious Life

2. Philosophy.

F. Christianity in the First Century CE

A. Overview of Ancient Mediterranean Cultures

While different ethnic groups reflected various structures and ideals, ancient Mediterranean cultures shared the social building block of the clan, along with attitudes that reinforced the extended family: hierarchy, social classes, reciprocity and patronage, honor-shame.

1. The Clan.

One institution dominated ancient culture: the clan. A multi-generational extended family lived in a single compound, plying a single trade. Bonded by blood, it created opportunities for economic, social and political ties within a community. It not only provided the social safety net for family members, it also defined the place of those individuals within the community. Loyalty to the group (family or community) was more important than any sense of self-determination.

2. Hierarchy in the Clan.

The clan inherently developed an internal hierarchy. In a male dominated, gender segregated society, patriarchs ruled the clan, followed by adult males, then female adults and boys, finally girls. Of course, this described a formal understanding of the family unit. Obviously, boys were males in the process of becoming men. And women did hold sway over their sons and brothers; they acted as advisers to their husbands and informal go-betweens with other clans. While males did rule, we should not underestimate the power of women within the extended family.

3. Hierarchy in Social Classes.

The notion of hierarchy reflected the organization of society in general. We, in the West, conceive of society as an association of equals, especially before the law. Ancient culture had no such notion. Instead of the horizontal, they saw kingdoms and empires integrated vertically, with class distinctions. However, one individual did not rule over another; one clan dominated another. The king was the patriarch of the royal family and that clan had a relationship with those beneath it. This system emphasized nepotism over merit.

4. Reciprocity and Patronage.

Reciprocity clued clan together with clan, forming communities, kingdoms and national identities. In its simplest terms, it meant an exchange of gifts. For example, hospitality was a major virtue in the ancient world. A host would receive a stranger, giving them room and board for the night. However, custom demanded some sort of repayment by the visitor, usually in the form of stories from his travels. For his gift of food and lodging, the host received an evening's entertainment from his guest.

Reciprocity also held sway between clans of greater and lesser classes. The rich patron provided economic assistance and political clout to the poor client. In return, the poor remained loyal to their benefactor, many times acting on behalf of their sponsor. Patronage cemented loyalties vertically, the largess of the wealthy demanded the allegiance of the common citizen.

5. Honor-Shame in Society.

Place in society played a major role in ancient culture. Honor and shame dominated public discourse. In a city, the rich civic leaders would finance religious festivals and civic improvements to shower honor on themselves. On the streets, some men employed slander and insult to pump up their reputation at the cost of another. Good people displayed their virtue, while the evil hide from view. Honor and shame motivated behavior in a far greater manner than life today. Reputation of the clan trumped the importance of its economic output.

6. Conclusion.

Ancient society possessed a group mentality. The place of the individual depended upon his place in the pecking order of the clan; relationships between clans trumped his personal concerns with outsiders.

Social welfare of the person depended upon well-being of the extended family, including its reputation. The honor of the clan gave it social, political and economic power especially in negotiating agreements with other clans. And its honor depended upon its place in the social hierarchy; the higher up the ladder, the greater the reciprocity that it could offer lesser clans, the greater the patronage it could command.

B. A Brief History of Greco-Roman culture.

The first century CE culture in the Mediterranean basin was dominated by the Greeks. But we must notice the classical social forces on mainland Greece and the islands of the Aegean vs. those spread by the conquest of Alexander the Great. His rise shifted the meaning of the culture from the parochial to one that embraced much of the world. The Romans adopted and adapted these latter forces into their culture, thus creating a hybrid ethos.

1. Classical Greek Culture as Urban.

Greek Vase

Before the rise of Alexander, Greeks saw themselves as an ethnic group that occupied the upper Greece, lower Greece and the islands of the Aegean, spreading even onto the coast of Asia Minor (modern day Turkey). They did not form a single nation under a monarch, but lived in independent city-states. The glue of their identity lie in a common language (with a standard alphabet), a shared pantheon of gods, the quadrennial Olympic games and trading ties; they also shared a focus upon urban life. Greeks organized their culture around the "polis" (Greek for "city," from which we receive our word "police" and "politics").

While the architecture and city layout of the polis influenced Greek culture, both were shaped by the intellectual climate of the times. The genius of their classical era lie in a certain separation of intellectual pursuits from religious thinking. In other words, philosophers, mathematicians and scientists of the time could discover and utilize concepts apart from any connection with the gods. Plato's philosophy described the height of this separation in his use of forms and matter. Forms were universal and eternal, living in the world of ideas, while matter existed in an ever changing world; forms revealed themselves in the repetitive shapes found in the material world. In the polis, an architect employed geometric rules to design buildings that pleased the eye with shape and proportion. An artist would sculpt a statue or fresco according to the ideal ratio of the human form. A city planner gave order to neighborhoods through the use of mathematics. Indeed, they imposed the world of ideas upon the polis to give it, not only function, but with a connection to the timeless.

The urge to place the ideal over the real did not stop with pretty buildings and street grids. Greeks saw their civic life ordered along intellectual lines. They divided class along social lines with certain rights and responsibilities. Free men had full legal and political life, along with full responsibilities to lead and serve in the defense of the polis. Females and underage children had no political rights but some legal rights (to own and inherit property, for example). Aliens had no political rights but full legal rights. Slaves, of course, had no rights.

While the polis had a hierarchy of classes, what was the best way to organize that structure? We modern Westerners would argue for the most practical, but ancient Greek culture sought the most ideal. Plato argued against a democracy of the free men, but for a caste system of workers, warriors and enlightened rulers. These three levels paralleled the three aspects of the soul: the appetite in the digestive area (akin to the base nature of the common worker), the emotive spirit (like the qualities a brave and adventurous soldier possesses) and reason (likened to a morally good and wise ruler). Just as reason needed to control emotion and baser needs, by analogy Plato argued society required a philosopher king, a regent who possessed both the vast education and temperament to rule for the good of the people. But, who embodied such a man?

2. Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) and Hellenism.

Alexander the Great

With the death of Philip II of Macedon, his son, Alexander, continued the royal plan to put their Persian enemies at bay and consolidate their power in Greek world. By the time of his death ten years later, he had subdued Persia, conquered the eastern Mediterranean basin and pushed into India. In that decade, he also transformed the meaning of the word "Greek."

Ethnic Greeks considered Alexander an outsider and usurper, who spoke with either a foreign language or a guttural dialect. Yet, he imposed a common dialect ("koine" Greek) on the known world as the franca lingua. He founded cities in foreign lands on the model of the polis, thus creating new centers for political, economic and social life; through these new urban developments, Greek culture spread. On his death, his generals split his empire into three kingdoms with Greek-speaking aristocracies; these nations would survive until their defeat and absorption by Rome. From the time of Alexander well into the Roman era, the term "Hellene" (Greek where we get the word "Hellenism") did not exclusive refer to the native born of Greece, but to those who spoke the language and adopted the culture as their own. (In John 12:20, the term "Greek" had this broader meaning.) The Greek language was now the world language, its culture the world's culture.

How could Alexander shift history so quickly? True, he was a brash warrior-king with a seasoned army at his disposal. But, he also possessed the foresight to integrate local sensibilities into conquests. Not only did he allow people who surrendered to him to maintain their gods, he added their gods to his. He even adopted the Persian and Egyptian customs of ruler cult, worship of the divine in their kings. An acceptance of foreign gods ("you worship my god, I'll worship yours") and ruler cult marked Hellenism after his death.

Because of his cunning on the battlefield and his foresight in dealing with his enemies, Alexander epitomized Plato's "enlightened" ruler, the philosopher king. (Of course, his time as a youth studying under Aristotle only padded his reputation.) Later generations would look to Alexander as the prime example of the ideal ruler.

3. Rome's expansion into the eastern Mediterranean.

The city-state of Rome grew into a regional power on the Italian peninsula about the same time the Macedonia rose up. As the Romans thrust north, they conquered the Etruscans whom the Greeks influenced. As the Romans pushed their way south, they came into direct contact with Greek colonies in the peninsula boot and Sicily. Thus, they came to know this ancient culture first hand.

As Rome's world view expanded, so did it's appetite for control. Despite the two Punic Wars with Carthage (264-241 BCE and 218-201 BCE) in the western Mediterranean, it did exert influence over Greece in the third century BCE. With the conquest of its enemies in Northern Africa, it turned its attention eastward. In the first half of the second century BCE, Roman legions defeated various powers in Macedonia, Upper and Lower Greece, climaxing in the sack of Corinth in 146 BCE. Their voracious appetite for brutality knew no bounds. Between the mass murders, the enslavement of tens of thousands and the plunder of art treasures, the Romans de-populated Greece and sent it into steep economic decline. Yet, they also realized the value of their booty. They shipped many Greek slaves to the capital city as tutors for their aristocratic sons; they decorated their temples and personal homes with the sculptures produced by Greeks. While Romans considered Greeks duplicitous and two-faced, they not only recognized, but embraced Hellenic culture as superior. This set the stage for the Greco-Roman culture of the first century CE.

4. Augustus and Greco-Roman culture.

Augustus

(r 27 BCE - 14 CE)

Between 146 and 31 BCE, Rome completed its conquest of the eastern Mediterranean when Octavian defeated Marc Antony and Cleopatra at the battle of Actium. It absorbed the former Hellenic kingdoms established after the death of Alexander, but in no way tried to assert Latin culture by founding new cities or by imposing a foreign language. Indeed, it merely sought to lay a new political reality upon already existing culture structures, even adapting them to the new order.

Octavian, now Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE), established himself as the "Princeps," or "First Citizen" of Rome. He took upon himself various civic titles and powers in the city as window dressing for the shifting political landscape. Since Rome had been a republic, it detested anything smacking of regency. So, he merely repeated what the empire did to its subjected peoples; he built upon what already existed and consolidated power below the surface. He lived in a humble fashion, yet tilted the axis of control from the city fathers to the army. Once a force of conscripts and volunteers, the imperial army was a professional force of twenty legions (5,000 men each for a total of 125,000). Military service shifted from patriotic duty to allegiance towards the general who provided the soldier's pay, and, ultimately, to the general's leader, the emperor.

Augustus used Hellenism to his own advantage. He accepted ruler cult from the East and quietly promoted it in the West. Soon, busts of the emperor appeared in temples along side those of the gods; offering incense before the image not only honored the divine spirit of the emperor, but acted as a sign of tribute to Rome.

Augustus began a building campaign of unprecedented magnitude, rebuilding over eighty temples in Rome and beefed up the infrastructure throughout the Empire, Much of this new construction employed Greek architects and designs. But the Romans built on a scale unimagined by the Greeks, creating imposing buildings, grand public works and huge gathering places, heavily influenced by Hellenism. Through his beneficence, he modeled himself along the lines of Alexander and image of the "enlightened ruler."

Augustus promoted the revival of the old religious cult. Piety waned in the first century BCE. He blamed the disruption of the civic wars after the death of his uncle, Julius Caesar, on the decline of religious values. The displeasure of the gods resulted in chaos; their approval of his renewal resulted in his rise to power and restored order. But, since the Romans merged their notion of the divinity with the Greek pantheon by 217 BCE, Augustus appealed not only to the gods of Rome, but to those known throughout the Mediterranean. He ruled by divine favor.

Augustus built a propaganda machine, disseminating his image on busts struck for local towns and on coins minted by the millions. His popular image shifted from the realistic style of the Romans to the more idealized form of the Greeks. He even commissioned authors to compose Latin works in a Hellenistic style. Virgil produced the "Aeneid" which used the Greek form of the epic to re-imagine Roman identity; in the story, the Romans descended from the Trojans. Horace celebrated the emperor's achievements in the "Centennial Hymn." Rome's "First Citizen" thus used every means available to tighten his control, both through politics and through levels of culture at his disposal.

5. Brief History of the Empire

during the First Century after Augustus.

Three families controlled the imperial throne during the first century CE: the Julio-Claudian dynasty, the Flavians and the Nerva-Antonine dynasty. As such, they ruled during the life of Jesus, the apostolic era and the beginning of the post-apostolic age of the Church. During their reigns, Hellenism reached a new plateau of popularity in Rome; indeed, more than half the city spoke Greek as a first language.

The main sources for this era come from historians Suetonius (69-122 CE), Tacitus (56-120 CE) and Roman governor Pliny the Younger (61-113 CE). Suetonius wrote gossip-filled "Twelve Caesars" while Tacitus penned his magisterial multi-volume work, "Annals." We must be aware the Flavians sponsored the writings of these two historians; to pump up the reputations of Vespasian and his sons, they soiled the memories of the previous emperors. Nevertheless, most scholars consider their reports on Christians (detailed below) as factual. They also respect the correspondence between Pliny and the emperor Trajan for its candor on the matter of Christians.

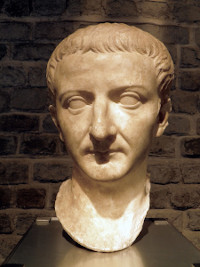

1) Tiberius (14-37 CE)

Tiberius

Tiberius was the stepson and adopted son of Augustus. Rising to favor as a successful military commander, he succeeded to the princepate in line with Augustus' will. Eventually, the political atmosphere in Rome turned toxic when he turned the daily operation of the Empire to a social climber named Sejanus.

Sejanus controlled a network of informers and spies in the capital; their charges produced treason trials that touched every faction of the aristocracy. The emperor relied on his henchman to root out any potential rivals, but his increasing paranoia turned against the lackey. When Sejanus overplayed his ambitious hand, he was betrayed by Tiberius before the Senate, purging him and most of his party.

According to the historian-critic Suetonius, Tiberius led a life of cruelty and debauchery on his estate at Capri. He died at Misenum at the age of 78.

2) Caligula (37-41 CE)

Caligula was the great-nephew and grandson (by adoption) of Tiberius. Suetonius charged him with perversity, cruelty and sadism, to highlight his alleged insanity; the historian reported the emperor presented himself in public as one or another of the gods. However, he strove to expand the power of the emperor while directing his patronage to ambitious construction projects and personal dwellings. Many in his court, those among the Praetorian guard and several Roman senators conspired against him; in January 41 CE, a group of Praetorian officers murdered the emperor. The public blow back from the assassination led to the death of the conspirators and eased the way for the quick succession of Claudius.

3) Claudius (41-54 CE)

Claudius

Out of fear for his throne, Caligula had much of his extended family murdered, except for his uncle Claudius. The emperor considered his older relative so physically and mentally feeble that he ridiculed him and did not consider him a threat. When a few of the Praetorian guards assassinated Caligula, other guards panicked, searched the palace and found a cowering Claudius. They immediately declared him emperor.

Suetonius mentioned one piece of information relevant to the Christian movement during the emperor's reign. He wrote, "Since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, he expelled them from Rome." Most scholars interpret the name Chrestus as a reference to Christus. In other words, disturbances broke out between Pharisaic Jews and Hellenistic Jewish Christians over the identity of the Messiah; they spilled out into the streets and caught the attention of Roman officials. In a city of a million inhabitants, these fights became riots that required the action by the emperor. So, Claudius banished those involved from Rome.

Claudius was vilified by Suetonius as an embarrassment to the imperial family. But the emperor did have success in his military campaign against the Britons and in his infrastructure projects. He died after eating a poisoned mushroom most likely supplied by his wife, Agrippina, the mother of Nero by a previous marriage.

4) Nero (54-68 CE)

Nero

Nero became emperor at the age of 17. In the first years of his reign, he found himself torn between his advisors, the poet Seneca and Burrus, and his mother. Over the next few years, he asserted himself, reducing the power of his advisors and sweeping away his mother from the court. He ordered his mother murdered in 59 CE. He consolidated power throughout his reign, ordering executions of rivals on trumped up charges, having others poisoned and forcing some to commit suicide.

Nero loved all things Greek. As the leading cultural leader, he popularized Hellenic song and competitive games. He styled himself as an Olympian: racing chariots, playing the lyre and composing poetry. He instituted Greek games in Rome, called the Neronia; traveling to Greece, he competed in all the pan-Hellenic games (and naturally won every competition he entered, whether he finished it or not). Granting tax relief to mainland Greece, he declared himself its "liberator" in 67 CE, spurring its moribund economy; Vespasian rescinded the relief during his reign.

According to Tacitus, in July 64 CE, a large portion of Rome burnt, inflicting great damage and fatalities on the city. Looking for a scapegoat to quell popular discontent and deflect blame, Nero persecuted local Christians. The passage from the historian acknowledged that Romans knew enough Christians lived in the city to be noticed by imperial officials, they could tell the difference between followers of the Nazarene and Jews, and they connected local Christians with their leader who died in Judea under the procurator, Pontius Pilate. Most modern scholars consider the passage to be authentic and not a Christian addition to the Annals. It stood as a an independent source for the death of Jesus under the Roman official.

Towards the end of his reign, the eccentric and moody Nero made too many enemies, both among the ruling elites and the army. Revolts in the Germania and Hispania provinces led to discontent among some Western legions. Soon, political support began to crumble and some in the Senate moved against him. Feeling cornered, the emperor persuaded his private secretary to kill him.

1) Vespasian (69-79 CE)

Vespasian

With the lack of heirs to the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Rome fell into chaos. Four emperors ascended the throne in quick succession; three of them were assassinated, the fourth committed suicide. The Year of the Four Caesars ended when Vespasian was declared emperor by his troops in Judea (suppressing the Jewish revolt of 66-70 CE) and by legions in Egypt. Joined by other forces in the East, troops loyal to Vespasian defeated the current emperor, Vitellius. The next day, the Roman Senate official named him the new Princeps. The civil wars came to an end.

Vespasian first took control of Egypt, the bread basket of the Empire, then moved to Rome in 70 CE. During that time, he consolidated power and quelled revolts, including mop-up operations in Judea. With the Empire finally at peace, he reformed the army, ranks in the Roman aristocracy and instituted a propaganda campaign. He minted coins with emphasizing his military victories and the new Pax Romana. He paid writers, especially historians like Suetonius and Tacitus, to burnish his reputation at the cost of the Julio-Claudian emperors. He also suppressed some descent. He continued infrastructure projects like temples and public baths; his most famous addition to Rome was the Colosseum.

Vespasian died of dysentery in 79 CE.

2) Titus (79-81 CE)

Upon the death of his father, Vespasian, Titus rose to the throne. He was well respected as a military commander, completing the subjugation of Palestine with the successful sieges of Jerusalem and Masada. He completed the Colosseum and provided aid to the victims the Mount Vesuvius eruption in 79 CE. He died of a fever in 81 CE.

3) Domitian (81-96 CE)

Domitian

As the son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, Domitian was named emperor by the Senate the day after Titus died. Before his ascension to the throne, he enjoyed little favor by the family; he served in ceremonial roles and suffered under the long shadow of his older brother. As the new Princep, he shifted power away from the Senate to his court and thus ruled as a new "Augustus," an enlightened autocrat in a divine monarchy.

Domitian ruled efficiently and scrupulously, bypassing family members for loyal ministers, patricians for those of the equestrian class. He stabilized and revalued the currency upward; he strictly enforced taxation that kept corruption to a low level. He invested in an ambitious public works project to rebuild Rome from the civil wars and the fire of 80 CE; the level of these projects equaled that of Augustus a century earlier. He also bankrolled cultural works of public banquets and expanded athletic competitions. In military matters, he preferred defensive posture and negotiations, but he did engage in several campaigns to quell unruly provinces. He traveled for three years to visit his troops in the field and beefed up the Germanic border with infrastructure. In questions of religion, he vigorously promoted the ancient Roman gods, including imperial cult and stressed ancestral worship, even deifying deceased family members. He spent heavily on temple construction and renovation. He insisted upon strict morals among officials and stifled any public criticism. In sum, Domitian ruled effectively but created an air of fear among the elites.

Because he drew all power to himself and micromanaged so many sectors of life in the Empire, Domitian quickly created enemies within the Senate and among the upper classes. A court official assassinated him in 96 CE.

1) Trajan (97-117 CE)

Trajan

Upon the death of Domitian, the Roman Senate appointed an elderly statesman, Nerva to the throne. Since he had no children, he adopted Trajan as his heir.

Trajan was the son of a noted senator and served with distinction in the army. Rising to the rank of general, he became one of Nerva's best officers. With his pedigree and his effective leadership in the field, he was a natural fit to rise to the throne. He did so after Nerva passed away in January 97.

As the governor of Bithynia-Pontus (in modern day Turkey), Pliny the Younger corresponded with Trajan on the matter of Christians. The pagan population considered them impious and anti-social; even treasonous for their rejection of imperial cult. Locals considered the increasing numbers of converts as a threat to social stability. If believers were brought before the governor for judgment, how should they be judged? Pliny opted on the side of caution, interrogating the accused three times before ordering them executed, giving them every opportunity to recant and offer worship to the gods. He released those who did give up their faith or denied they were ever Christians. In his response to Pliny, Trajan urged a reactive stance; the governor should not pursue Christians or allow hearsay in court, but should continue to punish the guilty and pardon the reformed. These letters marked the first evidence on Roman legal proceeding against Christians; they also contain pagan reports and prejudices on religious practices among the faithful.

Trajan expanded the Empire to its greatest extent, oversaw a large infrastructure program in Rome and enacted social welfare policies. He was considered one of the "Five Good Emperors." On his way back to the capital from a military campaign, he died in 117 from a fever.

6. Conclusion.

In the four hundred years from Alexander to Trajan, the Mediterranean region shifted several times, politically, militarily and culturally. The conquests of Alexander changed Greek language and culture from the parochial to the universal, thus creating Hellenism. The generals who succeeded him carved up his empire into three kingdoms: Macedonia, Syria and Egypt. In doing so, they established a Greek aristocracy in eastern Mediterranean basin. But, the Rome replaced these Hellenist realms in quick succession with its own rule. The Latin city-state expanded into an ancient superpower.

When Rome conquered the Greek mainland, it stripped the cities of their art work and enslaved its citizenry, bringing both back to the capital. The works inspired the Roman elites and the Greek slaves became tutors to their sons. After several generations, Hellenistic culture both dominated the Roman world and spurred Latin culture to new heights. By the first century CE, most cities in the Empire were multilingual, multicultural and multi-ethnic.

Once Rome lauded its status as a republic and disdained any hint of monarchy. Yet, in times of emergency, its Senate would appoint a dictator with powers to restore order. Under Octavius/Augustus, this state of affairs became permanent. The extent of the Empire required the office of emperor to administer such a diverse area. But, with one man rule came one man institutions. While "Princeps" meant "first citizen," in reality, the term merely masked the Roman version of a Hellenistic king, an absolute monarch with all the trappings of ruler cult. Some like Augustus and Trajan hid the reality well; others like Domitian didn't pretend to be anything less than a king. Even with the intrigue of palace coups and civil wars, the office of emperor stabilized the region and created almost 200 years of peace within its border (of course, Judea would be the exception to that rule).

Because of his wealth, power and status, the emperor drove the culture in the first century CE. His example (like Nero's obsession with all things Greek) set the tone for fashion. His largess created infrastructure projects that left his stamp on urban living, in architecture, in sculpture and other arts, in writers he underwrote and promoted. As Pontifex Maximus or chief priest for Rome, he directly influenced the pagan piety in his day. Those in the capital would follow his lead; those in the great cities of the Empire would certainly take notice and adjust their practices accordingly. With Augustus as his example, he employed every cultural means at his hands to burnish his reputation and extend his influence: minting coins with his image, erecting his busts and statues in public places throughout the Empire, promoting ruler cult, granting tax relief and trade concessions to cities for their loyalties.

In many ways, the rise of the Princeps brought the institution of the Hellenistic king full circle. The notion of an absolute ruler morphed from an eastern despot to a western one but maintained some of the same trappings.

D. Empire's Geography and Infrastructure.

At its greatest extent under Trajan (98-117 CE), the Empire encompassed 3.1 million square miles, from isle of Britain in the west to the mouth of the Tigris-Euphrates on the Persian Gulf in the east, from France and the Danube in the north to the Sahara in the south. Fifty five to sixty million people lived within its borders, between one sixth to one fourth of the world's population. The majority of those inhabitants clustered around the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, called "mare nostrum" or "our sea" by the Romans.

Rome ruled the Empire through a strong central government, the cooperation of providential governments, and a small but flexible military. As stated above, the army numbered upwards of 200,000 professional troops; each soldier served a twenty year term (plus five years as a reservist). Rome used its military not only the keep the peace, it employed them for infrastructure projects. The legions were kept busy with bridge building, constructing aqueducts and harbors, even the raising of city walls, all to keep troops physically fit, to give them a sense of purpose (thus avoiding mutiny) and to build up goodwill with loyal citizens.

Their road work stood out. To facilitate the rapid movement of legions, the army built a road system on a magnitude unimagined up to its time, over 50,000 miles of paved roads. It constructed roads linking Rome over the Alps to the roads build in Gaul; it also connected the city's Via Appia to the Via Egnatia that weaved its way through Greece and Asia Minor, eventually linking with the Persian Royal Road to the East. It built a system of roads on the African shore of the Mediterranean.

The military presence extended to building and maintaining way stations placed every sixteen to nineteen miles along major roads. It maintained the peace and encouraged settlement at these places of rest. While way stations required the display of passports by travelers, they spread a sense of safety, thus spurring traffic, trade and travel along their routes. Indeed, use of the road system grew to such an extent, it required hospitality of home owners to anyone traveling, by law.

Finally, the Roman navy tamed the Mediterranean and those regions with major rivers. Again, the primary use of ship was the quick movement of troops. Without any major naval threat in the first century CE, the Roman navy turned towards keeping the peace and suppressing piracy, thus encouraging travel and trade by ship.

While the road system and the sea lanes first and foremost served military function in the Empire, they boosted the movement of people and goods. Under the Pax Romana, both flourished, allowing the spread of the Good News across the Empire.

E. Urban Life in the Empire: the Polis.

As mentioned above, Greek culture throughout antiquity was urban. It took root and flowered in the polis. So, we should now turn to the structure of the polis and list the great Hellenistic cities in the first century CE.

In structure, the polis consisted of villages or neighborhoods clustered around a city center. That center contained a large open area for commerce, called an "agora" or marketplace. Close to the center, a high point was created as an "acropolis" or citadel, containing a temple, usually dedicated to the patron deity of the city. Various temples and altars were sprinkled around the center, reflected the polytheism of the times. Other amenities included a gymnasia and theaters (for presentation of plays, speeches and religious festivals). In it's later development, designers planned new cities along grid lines that emphasized not only order, but focus upon its center and institutions. By focusing the cultural, religious and commercial life of the city in its center, the polis could exert control over the outlining rural areas.

1. Structures in the Polis

a. The Agora. The commerce within the agora brought together peoples of various classes, buying and selling, haggling and bartering, creating a sense of social cohesion. The agora also provided a gathering area to hear not only gossip but town criers who hawked wares and announced official news, along with preachers who shouted to spread their philosophies. Of course, that did not stop shoppers from heckling those criers and philosophers. In the hustle and bustle of the agora, not only did money and goods exchange hands, there was also an exchange of ideas.

b. The Acropolis. As the high point of the polis, the acropolis acted not only as the citadel people looked up to, it was pinnacle of their aspirations and loyalties. Citizens rallied around the temple on it and the deity's statue housed within. As such, worship of the polis patron emphasized both patriotism and piety. No doubt, the rich built and maintained its temple as a gift to the citizens; civic pride pushed designers to create the worship edifice to be more beautiful and ornate that those in other cities. Such competition encouraged the development of architecture and the visual arts.

c. Other temples and altars. Within their polytheistic world, Greeks accepted the other gods within their own cultural pantheon. They also adapted foreign deities but grafting one of their a gods or demigods upon it, thereby morphing the identity of a strange deity into a new, more familiar one,

Each temple or outdoor altar included a wall to separate the sacred area from the profane. Most of the time, no dedicated clergy existed; the civic fathers led the city worshipers in sacrifice. These rich and well connected financed the religious festivals and, so, had the privilege to act as priests.

In Acts 17:16-34, St. Paul addressed the Athenians about their altar to an "unknown god."

d. Gymnasia. The gymnasia (from which we get the word "gymnasium") was a training center for free men competing in public games. It also acted as a male social club which housed an exercise area, communal baths and lecture room for philosophical presentations.

The term "gymnasia" came from the Greek word for "naked" (gymos). Competitors would train and compete in the nude as a way to emulate and honor the gods.

In Maccabees 1:14-15 and 2 Maccabees 4:9-14, the establishment of a gymansia and its games by the Hellenized leaders in Jerusalem offended the common people. Naked men violated their sense of modesty and the competition itself smacked of idolatry. This only added fuel to the passions that broke out in the Jewish revolt against the Syrian dynasty in 167 BCE.

e. Theater. Greek built their theaters in an outdoor, semi-circle, "amphitheater" style. It meant to seat a large segment of the population for religious and political functions. After a long procession, a religious festival would climax with a sacrifice to the god in the theater. During times of decision or crisis, the free men of the polis would meet there to discuss and approve plans of action; ancient democracy reached its full flowering in these gatherings. Soon, it became the place for the performances of plays, both tragedies and comedies.

2. Spread of the polis:

Major Cities in the East

The establishment of the Greek cities in the newly conquered lands created power centers for those who ruled after Alexander. The important ones were:

a. Alexandria (in Egypt). Founded by Alexander himself in 331 BCE, it dominated the western outlet of the Nile to the Mediterranean Sea. Strategically, it protected inner Egypt from foreign incursion and controlled trade. Exports of wheat and imports from other parts of the basin siphoned through the city. As it prospered, its population increased to include a large Jewish community and many ethnic Greek immigrants, along with local Egyptians. In the early second century CE, the city became home for a vibrant Church community.

b. Antioch (in Syria). Founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 CE, this city acted as the capitol for the Seleucid empire, one of the three Hellenistic kingdoms founded after the death of Alexander. In Acts, St. Paul visited the city many times, as the origin of his missions (Acts 13:1-3, 15:36) and its end points (Acts 14:26, 18:22-23).

c. Athens. This city was the epicenter of Greek culture during the classical period and clung to that tradition throughout the Roman era. During his military campaign of the early first century BCE, the Roman general Sulla devastated much of Greece, but left much of Athens' temples, civic buildings and monuments standing because of the respect he had for the city's cultural status. Many rich Roman businessmen and politicians endowed the city with infrastructure improvements; the emperor Hadrian spent lavishly on building projects for Athens. The city gained a good part of its income from cultural tourism.

Christianity made little headway in Athens. Paul's speech to the Athenians in the Arepagus (Acts 17:16-34) summed up the city's reaction to the new faith. The typical urbanite there, schooled in both philosophy and the traditions of the gods, had little time for a cult based upon a resurrected Savior. So, neither Paul nor any other missionary could establish a church community in the city. Indeed, a strong pagan presence remained there as late as the fifth century when the emperor Justinian ordered Athens' famous school of philosophy closed.

d. Corinth. The city strategically lay on the isthmus between lower and upper Greece. It acted as a civic check point on the road between the two land halves. And, it provided a layover destination for ships sailing between Italy and the eastern Mediterranean; a ship would dock at one of the two city ports and its crew would spend the night while it was dragged overland to the other port, then readied to set sail again. Because of its location, the city became rich from tariffs and other charges placed upon traveling peoples and goods. It also gathered an array of different ethnicities, different religious cults and different ideas.

The Romans destroyed Corinth in 146 BCE for siding against them in the Fourth Macedonian War. Julius Caesar re-founded the city in 44 BCE and it flourished as the administrative capital of Achaia. Paul visited the city in 49-50 CE and established the church community there. Because Corinth contained a mixed population of Jews, Greeks and Romans, it was fertile soil for evangelization. Unfortunately, it also teemed with the newest in ideas, since it acted as a stop over point for wandering teachers. Thus, Paul penned some of his sharpest critiques against the Corinthian church for their infighting and their openness to heterodox influences.

Many scholars believed Paul wrote up to four letters to the city church. The first was lost, the second comprised the canonical "First Letter to the Corinthians" and the last two were conflated into the "Second Letter to the Corinthians" (the fourth letter was found in chapters 1-9 and the third letter was edited to become chapters 10-13).

e. Ephesus. As a seaport along the Aegean shore, the city acted as the commercial gateway into the inner regions of Asia Minor. After suffering the ravages of war and sever reparations, Augustus named it administrative capital of Asia and it quickly prospered. While modern scholars argue over the size of the city, it stood as one of the largest in the eastern Mediterranean, comparable to Alexandria. Certainly, it housed important cultural institutions, along with major infrastructure: the famous Temple of Artemis, the Library of Celsus, large bath complexes, a vast water system with multiple aqueducts and an amphitheater that could seat 25,000.

According to Acts 19:1-20, Paul visited Ephesus. There, he laid hands on disciples of John the Baptist, disputed with both Jews who opposed the faith and witnessed Jewish exorcists who expelled demons in the name of Jesus, the One "whom Paul preaches." As a result of his preaching and spiritual gifts, many people there, including pagan magicians, converted.

The canonical "Letter to the Ephesians" differed in tone and language from other Pauline writings, even lacking the traditional greeting and goodbye. So, many scholars believe the letter did not come from Paul's hand but was composed in the post-apostolic era (80-100 CE?).

4. Conclusion.

Despite different ethnic mixes, the major cities of the Empire shared Hellenistic institutions that reinforced a common cultural identity. In the eastern Greek urban centers, the agora was the center of urban life, surrounded by temples and legal buildings. In the Latin west, the forum contained the religious and political institutions as the city center; the marketplace was next to the forum. Still, the important sacred spaces stood upon the high spaces; gymnasiums were common. Every major city had a theater that could hold tens of thousands for entertainment and religious purposes. While each city had its own distinct flavor, it shared social structures with other urban centers that created a feeling of familiarity.

F. Religion and Philosophy in the Empire

1. Religious Life.

Both Greeks and Romans believed in multiple deities, but the way they conceived of their gods differed. Greeks saw their gods as superhuman, anthropomorphic beings that represented forces of nature. Romans, however, were originally animistic; they did not ascribe forms to the forces they interpreted as divine. Overtime, they adapted Greek forms for their gods and adopted Hellenic deities as their own. In 217 BCE, they officially swept away any distinction between their gods and those in the Greek pantheon, indeed, giving Latin names to their Greek counterparts. Zeus became Jupiter, Hera became Juno, Athena became Minerva. But, Romans still experienced these gods more as forces than as vaunted humans.

Religion of any age has two aspects: the personal and the public. The personal emphasized the interior life with private prayer and practices that expressed devotion to a deity. The public stressed communal cult, marked by certain behaviors shared with others. Ideal religiosity balanced the personal and the public, but various cultures at certain times placed one over the other. First century CE defined piety as social. One's "faith" in the gods depended more upon participation in religious festivals with its processions, sacrifices and communion meals. Public piety was the glue that held communities together, but daily life did not lack for private devotions.

a. The private sphere.

Ancient Etruscan Amulet

1) Family demigods. Private devotion focused on one's personal needs. Since ancient culture did not recognize natural cause and effect, it held every phenomena was the result of spirit activity. Gods and demigods controlled every aspect of life, so personal piety involved reciprocity with these divinities. Making one's way through life meant saying the right prayer or offering the right gift to the spirit so the devotee could receive the expected reward. No activity was too small for some sort of ritual negotiation.

2) Honoring ancestors. Both Greek and Romans placed an emphasis on the family linage and the place of their ancestors. They burnished their reputations by basking in the glow of an honorable father or grandfather. Through prayer and ritual, they also evoked the spirit of those ancestors to give them strength in their daily lives. The wealthy even built elaborate burial monuments to honor those who had passed before them and give them a final resting place along with these great ones.

b. The public sphere.

Imperial Cult Temple

Maison Carree, Nimes

1) Worship area. Expressing piety in public demands a place: a gathering area for the faithful, an altar to offer sacrifice to the god and a wall to separate the two. A temple was an addition to these three, acting as a home for the deity. Unlike modern worship buildings designed for the people, it meant to house a statue likeness of the god and offerings before that god. While designers could incorporate the altar and separation wall into the temple, they could also place them adjacent to the building. In the first century CE, most temples in the Empire had Greek designs, since people considered this style as high architecture. Cities in the Empire would contain many altars and temples, especially around the agora, stressing the polytheism of the times.

2) Festivals. In many cities, religious festivals included a procession of the deity statue which began at the temple, weaved its way throughout the streets and ended with a cultic sacrifice in the outdoor theater. Leading men in the community acted as priests, invoking prayers and vows to the deity. These leaders also financed the festival for the good of the community, even distributing monies, grains, perfumes and the meat from the sacrifice to the participants. Since these festivals covered the entire city, most citizens took part in the festive atmosphere, joining in the procession, the prayers and the community meal which concluded the celebrations.

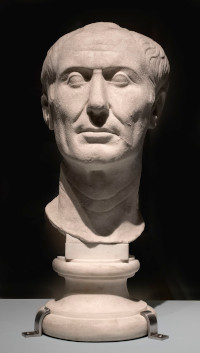

Bust of

Julius Caesar

3) Ruler Cult. We should not confuse this practice with adoring the regent as a god, but honoring them as close to the gods or having god-like virtues. Unlike the monotheistic notion of strict separation between the sacred and the profane, we can think of a continuum between the gods and humanity; the further up the social hierarchy, the closer one was to the divine. Certainly a conqueror, like Alexander (and later Augustus), who asserted such dominance and many times looked kindly on a vanquished people possessed the power of the gods.

After an emperor's death, the Roman Senate usually declared the former leader a god; in other words, they assumed the man's spirit rose to the level of the gods in heaven, so posthumous worship seemed appropriate. Since Augustus was the adopted son of his uncle Julius Caesar and his late relative was declared divine by the Senate, the first emperor used these facts to his advantage by naming himself, "filium dei," son of a god. In this way, he solidified his place as a force close to the level of the gods.

Subjects, especially in the eastern part of the Empire, felt compelled to honor the Princeps as close to the gods with his own dedicated image, altar and cult; in this way, they could gain imperial favor in questions of stature, tax relief and trade concessions. However, most emperors, beginning with Augustus, insisted any ruler cult include honor to the goddess Roma, the embodiment of power exerted by the city-state Rome. Any temple built for ruler cult also included an altar to Roma. Thus, the common people believed that the spirit of the leader and the State manifested the will of the gods.

Roman officials exempted Jews from ruler cult. Jews consisted of eight to ten percent of the Empire's population and remained intensely monotheistic; any imposition of a such devotion by Rome would result in unrest throughout the Empire. So, both parties reached an accommodation. To their fulfill obligations, Jews would pay annual tribute (a tax) to Rome and Temple priests would offer daily sacrifice in Jerusalem for the good of the emperor. Of course, Christians had no such work around.

c. Private devotion in the public sphere (so-called mystery cults).

Piety in the Empire did not begin and end with the official pantheon of gods. Many cults thrived in pagan culture, promising divine favor in return for zealous devotion. Some of them were:

Asclepius

1) Asclepius. Fathered by Zeus with a human mother, this demigod was the Greek deity of the healing arts. Since Greeks had immediate concerns about their health, especially where pain and suffering remained a constant fact of life, they naturally gravitated towards a devotion to this half-god. A pilgrim would visit a temple dedicated to Asclepius, undergo healing rites and spend the night in the holiest part of the sanctuary, awaiting a divinely inspired dreams. He would then relate his vision to the priest and receive a therapy from the holy man. Archaeologists have uncovered graffiti and cast off medical aides at the shrines of Asclepius as testimony by devotees to perceived cures. The symbol of this demigod was the staff and snake, adopted as the modern symbol of the medical profession.

Plaque of Mithras

3rd Century CE

2) Mithras. Romans adapted this Persian god as their own during the first century CE. Modern scholars point to this cult as a mystery religion, one with secret initiation dinners, underground temples and private rituals built around the sacrifice of a bull. While the cult cloaked itself in secrecy, ancient society tolerated devotion to Mithras partially because of its avid adherence among the western imperial legions. Indeed, the hierarchy of its priesthood mimicked the military chain of command. Since no written texts of this cult survived, their theology is contested by scholars; the archaeological evidence points to a belief system different from its Persian roots.

Roman Statue

of Cybele

3) Cybele (Magna Mater) The cult of the pregnant earth goddess originated in Anatolia (modern day Turkey) and passed to the Greeks. Rome adopted the goddess after the the Sibylline oracle recommended her worship during the second against Carthage (218-201 BCE). In the mythology of the city, she soon evolved into an ancestral deity from Troy to parallel the belief about the city's origins. In Virgil's Aeneid, she is the mother of Jupiter and acted as protector to Aeneas in his journey from Troy to Rome. Since the aristocracy of the city claimed ancestors among Aeneas and his fellow Trojans, they also promoted her cult as a way to burnish their own reputations.

In the first century CE, Augustus conflated Cybele (known as Magna Mater, Latin for "Great Mother") with the imperial order; in other words, the power of Rome and the forces of nature were indistinguishable. Emperors sponsored a spring time festival that expanded into a week of celebration. While these officially sanctioned feasts remained wildly popular, the cult itself remained closed; its leadership (Rome's elite) had its initiation rites.

Bust of Dionysus

4) Dionysus/Bacchus. Bacchus was the god of wine and wine production, fertility, theater and religious ecstasy. It soon grew into a mystery cult of ritualized abandon. According to the historian Livy, drunken men and women cavorted in sexual orgies, corrupting the morals of Roman society to the extent that they posed a threat to the State. Their secretive celebrations created rumors of subversion and even revolution. In the early first century BCE, officials arrested 7,000 adherents and executed a majority of them, thus suppressing the cult. The memory of the cult remained present in the minds of Roman officials years later.

Isis with Serpent

2nd Century CE

5) Isis. This mother goddess from Egypt paralleled the cult to Cybele. Isis developed from an ancient Nile deity into a Hellenistic god that spread throughout the Empire. According to the mythology, she was the first daughter of the earth god, married her brother deity, Osiris, and bore Horus, the falcon-head deity associated with regal power. Adherents explained the Nile's yearly flooding as Isis weeping over the death of Osiris; they saw the annual renewal of farmland from the floods as the resurrection of Osiris through the magic of Isis.

During the Hellenistic period, the cult spread in the eastern Mediterranean. The emperor Caligula (ruled 37-41 CE) established it in the capital; Vespasian (ruled 69-79 CE), his sons Titus (ruled 79-81 CE) and Domitian (ruled 81-96) built built up its worship with temples and partook in its cultic rites. The popularity of Isis remained until the demise of paganism in the fourth through sixth centuries CE.

d. Pagan holy men. Many self proclaimed ascetics/philosophers/wonder-workers wandered the eastern basin of the Mediterranean. The most famous of these in the first century CE was Apollonius of Tyana, a student of the Pythagorean philosophy which opposed animal sacrifice and encouraged a strict vegetarian diet. He traveled throughout northern Syria and Asia minor, gathering disciples. Philostratus wrote a biographical novel about the ascetic in the third century CE, posing him as a pagan alternative to Jesus. While the writer's "Life of Appollonius of Tyana" remained historically suspect, no doubt people believed the wisdom and wonders ascribed to the wandering philosopher applied to others during the first century CE.

2. Conclusion

We can see from this brief overview that paganism was not a monolithic reality, but had a diverse, ever changing flavor. The gods worshiped depended upon the locale, the political/cultural winds that blew across the region and the perceived power of the deity. Hellenism (and later in its Roman guise) promoted religious toleration based upon two principles: reciprocity and civic pride. People throughout the Empire took the view that "I'll worship your gods, you worship mine." And they mated that worship with with the spirit of community. Accepted behavior in the city meant partaking in frequent religious festivals.

But the spirit of reciprocity was not limited between peoples but between the worshiper and the worshiped. In the first century CE, most ancients assumed a tacit agreement existed between humanity and the gods, described as the "pax deorum." While the literal translation of this phrase was the "peace of the gods," it could be better translated as "peace with the gods," an arrangement where people would give proper worship to the gods in order to receive the proper blessing. Any lack in communal piety threatened that relationship.

Roman officials, along with the locals, tolerated Jews, for they had a long, distinguished tradition. But, the children of Abraham rejected the reciprocity of worship with their neighbors and involvement in the local festivals simply because they were strict monotheists. Because of their shear numbers in the Empire and their prayers for the emperor in the Temple, they found accommodation with their Roman rulers.

Judaism differed from their pagan counterparts in another sense. Jews were a people of the Book. In other words, they set their religion on a literary base that they transport from place to place. And, their writing contained a moral code for daily living. While other cults might have writings, they did not tie their worship to their books. Hence, they did not promote morality. To find an ethical lifestyle rooted in literature that appealed to the pagans, we must turn to the subject of philosophy.

3. Philosophy.

In 155 BCE, Athens sent three philosophers as ambassadors to Rome, Carneades from the Academy (Platonic school), Diogenes from the Stoa (Stoic school) and Critolaus from the Lyceum (Aristotelian school). These three represented the best in intellectual firepower Greek culture had to offer. While Cato had them ejected from the capital, the visit marked a turning point for philosophy in the capital. By the first century CE, it, along with other Hellenistic literature, was the rage among the ruling elite. It provided not only a cogent world view but the intellectual underpinnings for the moral code people strove to live by.

During this time span, three lines of philosophy stood out: Platoism, Stoicism and Epicureanism.

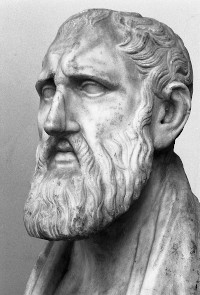

Zeno

334-262 BCE

a. Stoicism. In the early third century BCE, Zeno of Cituim founded Stoicism as a philosophy that unified all knowledge into formal logic, a physics of moism and an ethics based upon nature. This thinking sought to reconcile free will with determinism and create a balanced lifestyle. In the first century CE, most Roman and Greek elites focused on the ethical aspects of the philosophy.

Stoics did not strive for placid state of dispassion, but an emotional life that allow both moral and intellectual clarity. In other words, the will needed to control the emotions so the person could see the world as it truly was, conform himself to that world and, thus, find peace of mind. This was a state of equanimity between the highs and lows of life; it was also the ability to judgment actions clearly. When one had self-control, especially over the emotions, he could use reason, a understanding of universal thought that ran throughout nature, to live a virtuous life, an existence in harmony with nature.

Stoicism had a spiritual component. It saw all people as manifestations of a universal divine spirit, hence everyone possessed an inherent goodness. All shared equally in the human community; there was no distinction between social classes or ethnic peoples. How could a Stoic realize that divine spirit in himself and others? Through daily struggle of constant practice and self- reflection. This included Socratic dialogue, the contemplation of death, mindfulness training to focus on the present moment and review of daily life for solutions to problems.

While Stoics did see a certain equality across class lines, they did hold to certain determinism in societal structure; one was destined to be born rich or poor, so one should accept and make the best of one's position. This insight fit well into the Roman world view. Pax Romana was divinely ordained. The Empire should naturally rule the known world. This belief, along with a balanced emotional outlook ("gravitas" or seriousness) and a virtuous life marked the Roman elite as Stoics.

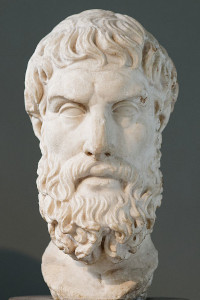

Epicurus

341-270 BCE

b. Epicureanism. In the late fourth century BCE, Epicurus taught a philosophy that sought a life free from suffering. Epicureanism held a materialistic view of reality based upon a physics of atoms. Unlike Stoicism's universal spirituality, this line of thinking saw the world, including the gods, as indifferent to the plight of humanity. Hence, it concluded the only inherent good was "pleasure," not in the sense of libertine hedonism, but as a state of tranquility and freedom from fear. Such a state could only be attained through modest living, an awareness of how the world works and limitations on one's desires. Moderation also meant withdrawing from many forms of social life, including politics.

Lacking any guiding universal moral principle, Epicureanism focused on the self. Since "pleasure" was the highest principle, it dictated any action an individual took must be weighed based upon benefit to the self. One measured moral norms on the continuum between honor and shame, between a life unencumbered and punishment. One acted virtuously only the please the self. One gained friends for the mutual benefits such an association provided. Since Epicurus did not believe in an afterlife, he taught that a happy life only occurred in the moment.

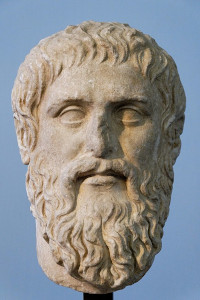

Plato

c 428-348 BCE

c. Platonism. Founded by its namesake in the fifth century BCE, this philosophy evolved to the first century CE and beyond. In a nut shell, it held reality had two components, the seen but unintelligible (matter) and the unseen but intelligible (forms). One experienced matter through the five sense, but this bodily contact alone did not explain the what, where, when, how and why of matter. One could only answer these questions by apprehending certain universal forms matter seemed to take. Like mental snapshots that a person compared and contrasted all the time, these forms existed outside the self. Hence, reality had three components, the tactile world of matter (particular and unintelligible), the realm of forms (universal and intelligible) and one's interior life where reason applied the ideas found in the forms to the experience of matter, thus making sense out of one's environment.

By the first century CE, Platonism shed its skepticism about certain knowledge and entered its next phase. Adapting many Aristotelian and Stoic teachings, Middle Platonists constructed a systematic world view of God, the world and the world-soul. God, as pure spirit, was all-good. The material world experienced both good and evil, order and chaos. As the intermediary, the world-soul housed the universal forms. Since these forms were amoral by definition, they acted as the organizing principles to the cosmos and the sources of evil.

However, since Middle Platonism argued for universal forms, it could also hold eternal norms of conduct, thus, virtues that existed outside the self (contra Epicureanism). It could also argue for a hierarchy of virtues ending in the highest form, the Good, which many equated with God. Soon, the philosophy developed spiritual practices. To reach God, they held, one must seek wisdom through contemplation, transcending the material world towards the divine. Plutarch (45-120 CE) held God could reveal his will directed through prophecy, bypassing the world-soul, thus granting the adherent wisdom. He also believed all the pagan gods were merely manifestations of the Good, so honoring the gods had inherent value (not unlike Hinduism). Centuries later, Platonists would argue for such a pagan monotheism contra Christianity.

4. Conclusion.

In the first century CE, most elites had a broad education in philosophy, especially Plato and those of classical Greek. But, these aristocrats had an eclectic outlook, picking and choosing teachings to sought their needs. However, we can safely assume those of the Latin west leaned to the Stoics, while the Hellenists in the east followed in the footsteps of Plato. But, because Stoicism and Platonism held to universal principles, they made natural allies against the self centered ethics of the Epicureans.

The intellectual descendants of Epicurus did have champions in the sophists, those who taught rhetoric among the rich and famous. A gentleman of the Empire not only had to think well, he needed to speak and write well. In the case of the Romans, that meant literacy in the Attic Greek of the classical period, as well as the newer works in Latin. Hence, the rhetorician played a vital part in the upbringing of the aristocratic males. They stressed the worth of the individual, his reputation and his social cache, depended more upon his oratorical skills than his ability to think on his feet. As the Greek sophist Protagoras (490-420 BCE) stated, "Man is the measure of all things." Such a sentiment fit hand in glove with the world view of the Epicureans.

Last, we should not conceive of these philosophies as strict schools of thought with hierarchies or sacred texts. The disciple of a particular philosophy usually taught as an individual, even practicing his beliefs as an ascetic. Yes, a community of disciples might form around such a thinker and even outlast him by several generations. But that was not the norm. Instead, philosophers cropped up as writers or teachers, even as "holy men" who wandered from city to city preaching their beliefs or who acted as the local crackpot, living out a strange, counter-cultural lifestyle to gain the attention of local inhabitants. Philosophers were as diverse as those preaching Christianity in America today.

G. Christianity in the First Century CE

Now that we have surveyed Greco-Roman culture in the first century CE, we turn to the place of Christianity in that culture. How was it different from ancient cultural norms and paganism itself? What allowed it to grow rapidly? Where did it grow the most? What historical evidence do we have for that growth?

1. Christians vs. Ancient Society

We must remember Christians placed their top priority on a devotion towards one person, the Christ. That relationship took precedent over clan hierarchy (Matthew 10:37) or patronage (Matthew 23:8-10). A disciple would implicitly be ready to endure shame for his faith (Mark 8:38 and 1 Corinthians 4:10). While the early communities did develop internal lines of authority (1 Corinthians 12:28), some did have a loose structure that allowed for dissent (1 Corinthians 3:3-4). Unlike the Roman obsession for order and its clear lines of authority, many early Christians who faced ostracism from their families banned together in new communities that did not function according to traditional cultural forms. Of course, this did not mean followers did not live in clans ruled by patriarchs who used patronage to strengthen ties with other families. It meant devotion Jesus trumped any and all other social concerns.

2. Christians vs. Pagan Religion and Philosophy.

In the first century CE, Christianity burst onto the scene with a different world view from its pagan counterpart. Paganism in a Roman culture sought the "pax deorum," peace of the gods, a divine order that controlled all things including the political landscape. Insuring that peace meant spiritual reciprocity, offering the right prayer and sacrifice, receiving the desired result. Under Rome, that result meant military victory to impose order and repress descent, to promote prosperity that brought the city bread, entertainment and wealth to the Eternal City, to recognize that the conquerors subdued others by divine will. Sure, the culture encouraged toleration of other gods and cults, as long as those devotions fit into the Rome's spirituality. If Rome felt its position threatened, it placed the blame on a disregard for the gods. Their deities were to be served and proper service insured peace.

Christianity turned that view upside down in three ways. First, it inherited its monotheism from Judaism. There was only one God, YHWH, and all others were false. How could one have peace with the gods if they didn't exist?

Second, it saw the only Son of God not as a demanding ruler, but as the servant. In Mark 10:45, Jesus declared, "For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve and give is life as a ransom for many." In Philippians 2:7, Paul wrote of kenosis, the self-giving abasement of the Christ who took on the form of a slave. In John 13:4-5, he took the role of a slave when he washed the feet of his disciples at the Last Supper. The notion of self-giving and service found its image on the cross, a sign summed up in the famous verse, John 3:16.

Third, Christian spirituality rejected reciprocity as its basis. No implicit understanding of "quid pro quo" could exist in a theology of grace, a term meaning "gracious gift." Disciples believed "you are being saved by grace through faith, This is not from your efforts; it is a gift from God." (Ephesians 2:8) In other words, a follower's relationship with God depended upon grace, from his faith to his moral living in a community to his afterlife. As a gift offered, not out of necessity but out of love, it could not be demanded or repaid. In this understanding, one could not possibly reciprocate in a relationship with the Christian God.

These last points led to the matter of morality. Like Judaism and unlike paganism, Christian ethics flowed from faith in God. Jews obeyed the edicts of the Law; their morality was a matter of duty. Average Romans and Greeks appealed to traditional social norms, while the elites leaned upon philosophical insights. Christians lived out morality through imitation of the Christ. He poured himself out for the good of others. The gift of that self-giving should be passed along to others. In other words, Christian ethics were based upon altruism; the disciple treated others the way God through Christ treated him. This way, he did not act based upon reciprocity, nor did he appeal to the "pax deorum" for the way he acted. Obviously, Christians rejected the pleasure principle of Epicurus outright; ethics were not self-centered. Nor did they feel comfortable with the determinism of the Stoics; morality was more than aligning one's self with the will of the gods, it was pro-active, based upon love.

Flowing out of the three points above, the community of believers itself presented a counter-cultural face to the society at large. The Church was an assembly with spiritual power. Unlike bands of philosophic ascetics who strove for divine union through rigorous intellectual and physical practices, the Christian community received various charisms as gifts of the Spirit. Their spirituality was not a quest to free the spirit from the pain and distractions of the material world, to rest in the serene world of the Platonic One. No, they received these gifts as an extension of grace, to strengthen the community and to evangelize. But the community did not merely consist of individuals with spiritual power; the Church itself was the center of that power, for, within its walls, one could experience the Spirit of God.

3. Spread of the Good News in the Empire.

No where else in the Scriptures does Rome's infrastructure shine brighter than in Paul's three missionary journey's. The apostle to the Gentiles traveled by land and sea for thousands of miles. During his three journeys (first trip in Acts 13:1-14:27, second in Acts 15:36-18:22 and third in Acts 18:23-21:16), he made his way from Antioch in Syria through Asia Minor, Macedonia, upper and lower Greece into Palestine and Jerusalem itself. After his arrest at the Temple, he appealed to Rome and made his way to the capital (Acts 21:16-28:31). His travels, along with the established church community in Rome, testified to the ease of travel people enjoyed during the first century CE, all thanks to the safe roads and sea lanes Rome strove to maintain.

4. Christianity as a city religion.

The commonality of a Hellenistic culture and its urban institutions provided fertile soil for evangelization. Along with Rome, most of the major cities in the Empire contained thriving church communities. We can surmise the faith found root in urban centers that shared Greek language and Hellenistic culture, but housed peoples from many different nations, including Jews. Because of its connection with Judaism, Christianity could offer Gentiles a faith immersed in a monotheistic tradition and a high standard of morality. With its apocalyptic world view, it could also give these people a sense of spiritual immediacy based upon charisms, rooted in Jewish prophecy. Finally, it provided literature that acted as a background for the Good News: the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures. What Jews shared in common in the Hellenistic world, so did Christians.

Some of the institutions found in these cities also united the new Christians in a counter-cultural lifestyle. Believers would not partake in civic activities that surrounded pagan religious festivals, whether in the streets, at the temple or in the outdoor theater. No right minded Christian would visit a gymnasia. While cities immersed in Hellenism gave birth to growing church communities, the institutions of the polis gave them rallying points to oppose. It was this shared urban environment that early Christians could sum up their lifestyle as "in the world, but not of the world."

5. Christianity's rise and place in the Empire.

As we have discussed, Jews in the first century CE had an accommodation with the Romans, but Christians had no such understanding with the government or their neighbors. By the end of the apostolic era, everyone realized this small band stood apart from Judaism. Like their Jewish brethren, Christians held to a strict belief in one God, but lacked a formal way to honor the emperor. Pagans considered them secretive and anti-social; soon, prejudice and mistrust spread to the point that sporadic persecutions popped up.

Yet, despite its rejection of popular piety and ruler cult, Christianity flourished. Suetonius and Tacitus, along with Paul's letter, gave us hints to the growth of the Church in Rome. By the mid 60's CE, imperial officials had noticed the expansion of the sect, the rift between Jews and Christians and the practices of the Nazarenes as counter-cultural, even anti-social. In the early second century CE, Pliny the Younger reported his legal dealings with Christians, as he recognized their growth and perceived them as a threat to the social order, even thousands of miles away from Rome. Two of these three writers also noted official prejudice that soon developed against followers of the Christ. Hence, the rise of Christianity and the backlash against it set the stage for the life of disciples in the Empire until the ascent of Constantine several centuries later.

Sources

Ehrman, Bart D. From Jesus to Constantine: A History of Early Christianity. Chantilly, Virginia: The Great Courses, 2004. Print.

Garland, Robert. Greece and Rome: An Integrated History of the Ancient Mediterranean. Chantilly, Virginia: The Great Courses, 2008. Print.

Johnson, Luke Timothy. Early Christianity: An Experience of the Divine. Chantilly, Virginia: The Great Courses, 2002. Print.

Photo Attributions

Greek Vase. British Musuem [Public domain]

Bust of Alexander the Great. British Museum [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]

Statue of Augustus. Vatican Musuem [Public domain]

Bust of Tiberius. Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]

Bust of Nero. cjh1452000 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

Bust of Vespasian. Originally uploaded by user:shakko [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

Bust of Domitian. I, Sailko [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]

Bust of Trajan. Glyptothek [Public domain]

Roman Empire under Trajan. Coldeel (talk) 23:07, 26 March 2009 (UTC) [Public domain]

Etruscan Amulet. Walters Art Museum [Public domain]

Maison Carree Temple in Nimes, France. Danichou [Public domain]

Bust of Julius Caesar. Museum of antiquities [Public domain]

Ascelpius. original file by Michael F. Mehnert [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

Marble relief of Mithras. Mm.srb [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

Roman Statue of Cybele. Getty Villa [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]

Bust of Dionysus. Raffaele pagani [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

Isis with Serpent. Los Angeles County Museum of Art [Public domain]

Zeno. Paolo Monti [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

Epicurus. British Museum [Public domain]

Plato. Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons