Pauline Letters

and the Life of Paul

Overview

I. Introduction

A. Equality and Devotion

St. Paul

by Rembrandt

Paul of Tarsus was one of those rare individuals in history; he was an original thinker. In his letters to the Romans and the Galatians, he propounded two revolutionary ideas that changed Western culture: the equality of people and the spirituality of devotion over duty.

In his letters, Paul argued "There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female. For all of you are one in Christ Jesus." (Gal 3:28) Until the apostle arrived on the scene, Jews considered non-Jews, even the "righteous Gentiles" who honored the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, at best as second class citizens. The Chosen People had the promises of YHWH as their birthright; conversion was the only recourse the uncircumcised had (Isa 56:6-7). Paul fought vehemently against that prejudice, maintaining that all who clung to faith in Christ, no matter their national background would be saved. The God of Israel was the God of all.

"But, Paul," his critics retorted, "the Law formed and defined Judaism. You're arguing against the importance of the Torah." He responded with a novel insight. Again, up to the saint's time, popular spirituality demanded duty first. Pagans fulfilled their obligations through cultic practice; Jews defined themselves through adherence to the edicts in the Pentateuch. Love of a deity grew out of religious behavior.

The apostle turned that insight on its head. For him, the Law defined morality but did not insure redemption. Behavior didn't save, but faith in Christ did (Gal 3:19-25). In other words, devotion trumped duty in the hierarchy of spirituality. One did not have to justify his or her relationship with God through obedience to the Law. The believer kept legal codes based upon love of Christ and of neighbor (Rom 13:10). For the apostle, morality based upon devotion stood superior to one rooted in duty (Gal 4:4-10).

Today, we adhere to the principle of equality of all before the law. And we weigh spirituality based upon intent as much as action. Both values trace their roots in the writings of Paul from Tarsus.

B. Unity, Charity and Apologetics

From the notions of equality before God and salvation via devotion, Paul stressed three more themes in his core letters: unity within the community, charity in the form of a collection for the Jerusalem church and his strident defense of his ministry.

If community members were equal based upon their love of Christ, Paul reasoned, they should exhibit a unity of faith and purpose. As 1 Cor 12:4-7 stated:

While there are many kinds of gifts from God, we all share the same Spirit. While there are different ways to serve others, we all share the same Lord. While we might do different jobs in the community, we all share the same God who does all these things in everyone. God gave each of us a way to show the Spirit for everyone's good.

Paul implied the survival of the community, as well as its relationship with God, depended upon internal cohesion. In First Corinthians, he criticized the turf battles of cliques vying for leadership (1 Cor 1:11-13); indeed, he wrote the letter to correct abuses (1 Cor 5, 1 Cor 6:1-11, 1 Cor 8, 1 Cor 11:14-22, 1 Cor 12:17-34, 1 Cor 13, 1 Cor 14) In Rom 12:4-16 and Gal 3:26-28, he stressed the unity of the community despite ethnic differences. He promoted a unity of mind, heart and spirit in the local churches that acted as a counter weight to the prevailing social norms of his time, not only for survival and evangelization, but in light of the afterlife (Rom 6:5).

Paul extended the notion of unity beyond the question of faith, spiritual gifts and communal practices. He envisioned unity of the Church through charity: collections from the Gentile communities of the Aegean basin for the poor in the Jewish-Christian mother church at Jerusalem. He continually focused upon these efforts as an integral part of his ministry right from the beginning (Acts 11:27-30, Gal 2:1, Gal 2:10). H e appealed for donations in his core letters (1 Cor 16:1–4; 2 Cor 8:1–9:15; Rom 15:14–32). In this way, he stressed the universality of the Church, an organic reality greater than the collection of individual communities.

Because of his theses of ethnic equality and devotion over practice, Paul faced fierce opposition from Jews, both from within the Christian movement and from without. He was criticized by those who assumed the divine promises found in the Hebrew Scriptures granted the Chosen People salvation as a birthright and an inherent superiority over Gentiles. He doggedly defended his stature as an apostle, especially in 2 Corinthians (2:14-4:4, 5:11-7:4, 11:1-15, 12:11-18). By maintaining his status as one the Christ sent (1 Cor 1:1, 2 Cor 1:1, Gal 1:1), he could assert his thematic theses based upon that commission (Gal 1:11-12). In other words, he undercut the arguments of the "Judaizers" by claiming divine revelation. Contra non-Messianic Jews, he engaged in rabbinic style argument against the necessity of circumcision for salvation (Rom 2:25-29, 1 Cor 7:18-19, 1 Cor 9:20-23, Phil 3:2-3, Gal 3:1-3). Thus, because of his zealous determination to defend the principles of equality, salvation by devotion and unity (both with each community and in the Church universal), Paul faced both internal and external opposition, even to the point of risking his own life (Acts 9:22-29, Acts 14:19, Acts 21:30-32, Acts 23:12-13, Acts 25:2-3).

II. Status of the Pauline Letters

A. Undisputed, disputed and questionable authorship.

Many scholars divide the twelve letters attributed to Paul into three categories: the undisputed (1 Thessalonians, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Romans, Galatians, Philippians, Philemon), the disputed (Ephesians, 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus) and those whose authorship remained an open question (Colossians and 2 Thessalonians). They judged the status letters based upon three criteria:

1. Writing Style. This includes grammar, vocabulary and overall literary structure.

2. Themes. Thematic considerations consist of both internal issues and social context.

3. Dating. This specifically refers to the relationship between details within the letters and events listed in Acts.

The undisputed shared the same vocabulary, grammatical style and themes, hence came from the same author; items within the letters fit more or less with events found in Acts. The disputed differed in terms, writing forms and subject matter from the undisputed; in some cases, these letters showed a development of thought that made a better sociological fit in a time after the death of Paul. Then, two letters did share some similarities with the undisputed but also revealed differences that made some scholars question the authenticity of Pauline authorship.

Analyzing style, grammar and themes the letters, along with dating them, provide us with insight into the faith of early communities Paul established and supported. We can appraise the writing and subject matter of the letters far more easily than establish a time frame of their publication simply because the clues remain cryptic in some cases. However, when we compare temporal passages with the events we find in the book of Acts and to those from pagan sources, we can assemble a reasonable timeline for the appearance of individual letters.

B. The historical dependability of Acts.

In my analysis of Acts, I argued the book should not be read as a historical text book of the early Church. Instead, we consider it analogous to a historical novel, a narrative with an overall thematic arc. In the case of Acts, that arc was the work of the Spirit through kerygma and charism. But this emphasis leads the modern reader to ask the question: how can we rely on the historical accuracy of the book, especially the journeys of Paul which correlate to his letters? We can defend the relative historical accuracy of certain sections within Act based upon three factors: the "we" passages of Acts, details from ancient secular sources that correspond with certain passages in the book and the argument of correspondence/simplicity.

1. The "we" passages

The famous "we" passages consist of those verses where the author shifted from third person ("he" or "they") to first person plural ("we") thus implying a first person eye-witness. They consist of:

Acts 16:10–17. On Paul's second journey, the author-companion joined the apostle at the top of the Aegean basin. They sailed from Troas to Philippi in Macedonia. There, they evangelized Lydia, the rich merchant woman.

Acts 20:5–15. On Paul's third journey, the author-companion again met up with the apostle at Philippi and sailed together, along with others, to Troas. After healing a young man who fell three stories, "we" sailed along the western Anatolian coast beyond Ephesus to Miletus.

Acts 21:1–18. The author-companion accompanied Paul on his last trip to Jerusalem. They sailed among the Aegean islands to Cyrus, then to Syrian coast and arrived in the port of Caesarea. After a few days, "we" made their way to Jerusalem.

Acts 27:1–37 The author-companion rejoined Paul for his transfer to Rome under guard. They sailed from Caesarea to Cyprus and transferred to a grain transport. Then, they endured the arduous journey across the Mediterranean to experience ship wreck at Malta.

Acts 28:1-16 After Paul ministered to the local leader at Malta, he and the author-companion made their way to Rome.

To sum up, the author-companion appeared during Paul's second and third journeys in the northern Aegean basin, then traveled with the apostle to Jerusalem. After Paul's arrest and incarceration at Caesarea, he accompanied the apostle to Rome. Based upon this information, we can speculate that the author-companion lived in the area of Troas, joined Paul's entourage, then migrated into the apostle's inner circle. We can also imagine the author-companion had the financial resources and personal freedom to join Paul on his final journeys.

Some scholars attribute shift from "he" to "we" to an anonymous redactor; to my mind, they have not mounted an adequate explanation of the shift beyond that of an eye witness or, possibly, a scribe-author who had a personal relationship with that witness.

2. Pagans sources

Fragment of

the Delphi Inscription

a. The Delphi Inscription

In Acts 18:12-17, Paul faced the proconsul Gallio in a Achaean court. In the early twentieth century, archaeologists found a plaque written by the emperor Claudius to the official at the temple to Apollo at Delphi, Greece. They dated the imperial tablet to the tenure of Gallio as proconsul, 51-52 CE. Based upon this historical detail, we have a time frame to anchor Paul's second missionary journey.

b. Other historical figures in Acts

We can find few persons of note that ancient sources have mentioned. 23:23-26:32 of Acts cited Felix, Festus and Herod Agrippa II.

1) Marcus Antonius Felix ruled Judea as a Roman procurator between 52-60 CE; he heard the initial case against Paul in Acts 24:1-26. His second wife, Drusilla was the sister of Herod Agrippa II. According to Acts 24:27, he held Paul in confinement for two years.

2) Porcius Festus controlled the province as a Roman procurator between 60-62 CE; he continued the case against the apostle in Acts 24:27-25:12.

3) Herod Agrippa II (ca 27-92 CE; Roman name "Marcus Julius Agrippa") ruled lower Syria and Galilee, beginning in 55 CE. Josephus addressed the tetrarch in his Antiquities. Agrippa and his sister Bernice heard Paul's case as guests of Festus at Caesarea Maritima in Acts 25:13-27.

Did Paul really face trial in Caesarea? No reasonable argument exists against this event. So, based upon the transition between Felix and Festus, we can reasonably date Paul's trial around 57 (Felix), then 59-60 CE (Festus and Agripp II).

c. Argument from Correspondence and Simplicity

The argument from correspondence asks the question: "Do the various events found in the Pauline narrative of Acts ‘correspond' with the facts as we know them?" Descriptions of travel both overland and by sea, along with urban settings, many affirmed by modern archaeology, argue for the veracity of many sections found in Acts. On his three missionary journeys, Paul traveled on established Roman roads and on sea lanes kept safe by the imperial navy. Consider the apostle's transport from Caesarea to Rome in chapter 27. The most efficient way was laid out in the text: catch a short connection to Myra on the Anatolian coast (Acts 27:1-5) then sail on a Alexandrian grain ship bound for the imperial capital (Acts 27:6). The description of the weather fit the late summer wind patterns off the southern coast of Crete (Acts 27:14). In the face of uncertain odds, the decision to lighten the load and make a run for Malta made some sense (Acts 27:16-20).

The details of life in the cities he visited also have been well researched by modern experts. Consider two examples. First, the pagan riot in Ephesus against the nascent Christian movement (Acts 19:23-41) reflected the fierce civic pride the Ephesians had in its temple to Artemis, considered one of the seven wonders of the world at the time. It also highlighted the threat a monotheistic faith presented to the local economy based upon religious tourism. Second, Paul's preaching in Athens focused on the city's cultural atmosphere (Acts 17:16-34). He debated with Epicurean and Stoic philosophers (Acts 17:18-21); the city had famous schools attached to each world view. The apostle then addressed those gathered to debate in the appropriate forum, the Areopagus (Acts 17:19, 22), noticing their paganism (Acts 17:23), tailoring his speech to their sensibilities (Acts 17:24-31), even quoting from one of their poets (Acts 17:28). Modern scholars have attested to the veracity of the social environment found in each city. An educated person with knowledge of the Mediterranean world could create the Pauline narrative. But simplicity argued for the reminiscences of a seasoned traveler over that of a imaginative writer.

While taken separately, these details alone do not absolutely insure the historical accuracy of Acts. But these, along with the historical figures mentioned and the Delphi Inscription, and woven with the "we" passages at critical points of Paul's final journey to Jerusalem and transfer to Rome, paint a reasonable picture of ancient life on the road in 50-60 CE. Hence, we can comfortably assume the general historical accuracy of the Pauline ministry in Acts (with the caveat that we depend upon the temporal details as reliable).

Now, we can assemble a general timeline for the life of Paul and place his letters within that continuum.

III. The life of Paul

To outline the life of the apostle and place his letters in that timeline, we must consider a different type of correspondence, the agreement between the letters and the book of Acts. While details found in some letters do fit explicitly into the narrative of Acts, others fit implicitly. Those letters that do not "correspond" with Acts' flow find a better fit in a latter sociological environment.

Let's begin with the two dates established by the pagan sources: Paul's trial before Gallio (51-52 CE) and his incarceration at Caesarea before Felix (57 CE based upon Acts 24:27), then Festus and Agrippa II (59-60 CE). These two act as the tent poles upon which we will hang our timeline. First, the Gallio incident (Acts 18:12-17) occurred during Paul's stay in Corinth on his second missionary journey. So, we can look backward and mark his life before this event. Since the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15:1-27, Gal 2:1) occurred before second journey, we can reasonably date that meeting between 18 to 24 months before the trial, based upon time of travel and extent of stays in various cities; it occurred in 49 CE. From this point, Galatians gives us a time frame for Paul's early days. Second, the Caesarea imprisonment gives us the starting point for Paul's travels and final destination in Rome.

A. Early Years of Paul

1. Years One through Ten CE: Birth of Paul

By comparing Acts and Galatians with Philemon 1:9, we can speculate on the time frame for Paul's birth (see the brief commentary on Philemon below for more details). He was a near contemporary of Jesus.

2. Details about Paul's Early Life

Unlike the Nazarene who grew up in the rural, semi-literate region of Galilee, Paul grew up in an urban environment, implicitly receiving a solid education under the noted Pharisee, Gamaliel, in Jerusalem (Acts 22:3). Both early Christian sources (Acts 5:34-40) and later Jewish writings (Misnah's Sotah 9:15, for example) held the rabbi in high esteem, both as a teacher/scholar and as a wise leader in the Sanhedrin. Some scholars dispute whether Gamaliel taught Paul one-on-one, in a school led by the scholar or by the teacher at all. Nevertheless, based upon the undisputed letters, the apostle knew how to argue as a rabbi and communicate in a utilitarian Koine Greek. These facts supported the report he was an educated Hellenistic Jew who lived in Jerusalem during the nascent years of the Christian movement.

B. Early to Mid-30's CE: Paul's Conversion

Conversion of St. Paul

by Caravaggio

We can find mention of Paul's conversion four times in the New Testament: Gal 1:13-17, Acts 9:1-22, Acts 22:3-16 and Acts 26:9-20. While the passage in Galatians did not detail the event like the three accounts in Acts did, it was followed by a time frame to the Jerusalem Council. Paul remained in inland Syria ("Arabia") before his first encounter with the leadership at Jerusalem (Gal 1:18-19). Afterwards his visit (Gal 1:18-19; Acts 9:26-27), he spent three years in coastal Syria and southwest Turkey ("Cilicia;" Gal 1:21). Finally, he returned to Jerusalem fourteen years later (Gal 2:1) to find a compromise with tensions between the present Jewish-Christians and the growing Gentile converts (the Jerusalem Council; Gal 2:7-9; Acts 15:6-21). Counting backwards from the date of the council (49 CE), we arrive at a date for Paul's conversion in the early to mid 30's CE. If we date Christ's crucifixion to 30 or 33 CE, we can clearly see Paul became a disciple in the dawning days of the Apostolic era.

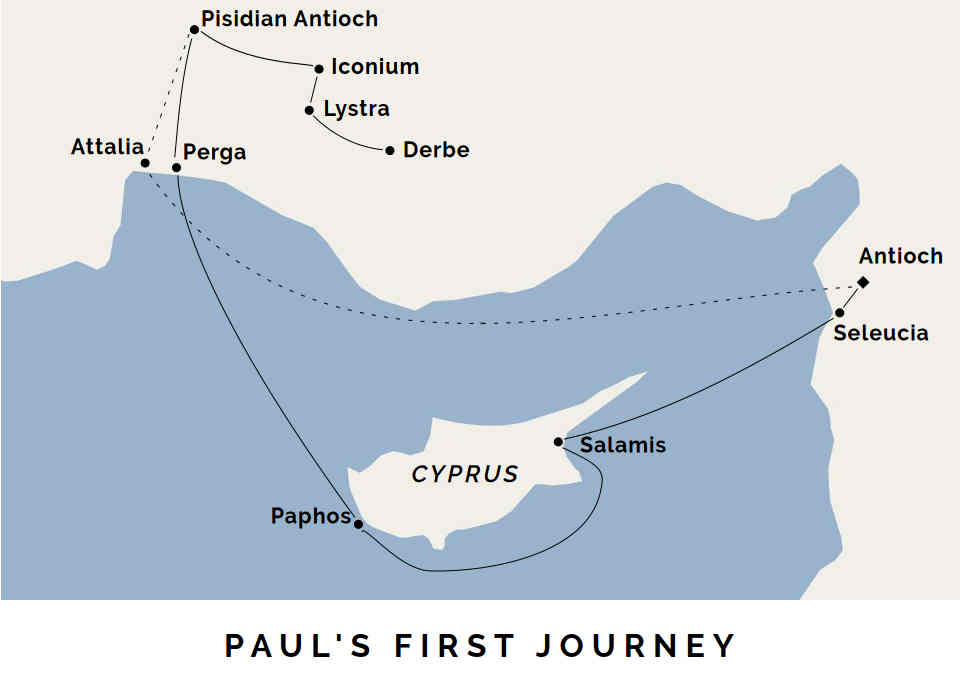

C. 48 CE: Paul's First Missionary Journey.

The apostle began his first missionary journey at Antioch in Syria (Acts 13:1-4), then sailed to the Cyprian port of Salamis (Acts 13:4-5), the island of Paphos (Acts 13:6-12) and landed at the Anatolian port of Perga in Pamphylia (Acts 13:13). He traveled inland to Antioch of Pisidia (Acts 13:14), then to Lycaonia, Lystra and Derbe (Acts 14:5-7). At this point, they retraced their steps through the area (Acts 14:21), then to the coast (Acts 14:24-25) and set sail back to Antioch (Acts 14:26). Paul and his companions reported their success in establishing new communities of mixed Jewish and Gentile neophytes (Acts 14:26-27); this ignited the controversy that led to the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15:1-5).

Paul and his entourage sailed to their destinations in a matter of days (depending upon prevailing winds). But they took far longer to travel overland (on average three miles per hour on foot, five miles per hour on horseback, depending upon the terrain). If we factor in travel time (about a month's length) along with stays in the various cities they evangelized and established faith communities, we can estimate the trip lasted from eight months to a year. Since it immediately preceded the Jerusalem Council in 49 CE, we can date the journey to 48 CE.

D. 49 CE: The Jerusalem Council

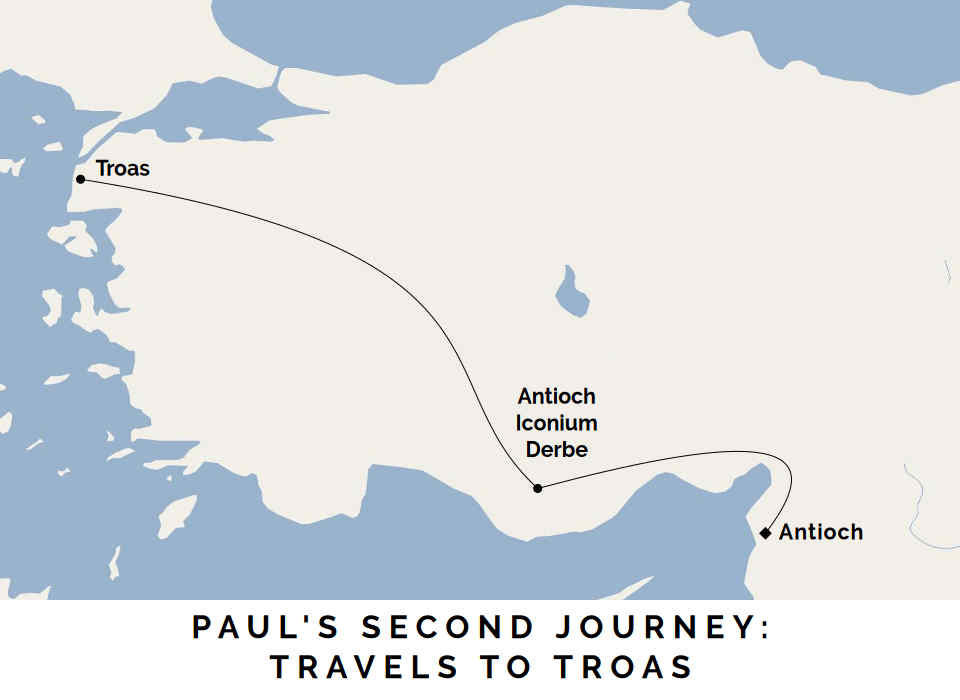

E. Mid-Late 50 CE to Summer 53 CE:

Paul's Second Missionary Journey

1. Travels to Macedonia

After the council, Paul and his companions returned to Antioch where he remained for, what we can assume, was several months. Here we can assume Paul confronted Peter (Cephas) over the question of mixed table fellowship (Gal 2:11-14); Acts did not record the incident. However, Paul split from his companion Barnabas over the presence of Mark (Acts 15:36-39), then proceeded to revisit the church communities he established via overland route (Acts 15:40-16:5). Through spiritual discernment, Paul decided to push northwest across the Anatolian peninsula to the Aegean port of Troas (Acts 16:6-7). On this leg of his journey, he and his companions traveled over 1300 km (800 miles), climbing over the interior highlands. If we factor in the stays at the churches Paul visited along the way, his travel time lasted four to six months from Antioch to the Aegean.

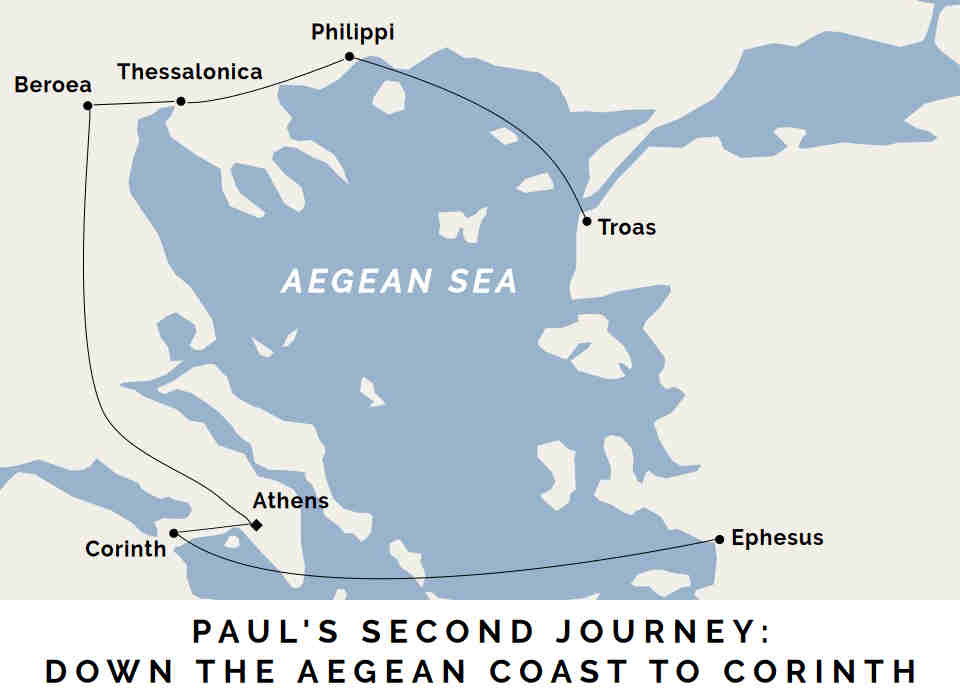

2. Down the Aegean Coast to Corinth

After his vision at Troas (Acts 16:9), Paul and his friends sailed for region of Macedonia and evangelized in the city of Philippi (Acts 16:10-12). Then they evangelized down the eastern coast of the Aegean at Thessalonica (Acts 17:1-3), Beroea (Acts 17:10) and Athens (Acts 17:15). Since Paul walked overland from Philippi, his efforts to establish communities along the Greek coast probably took another six months or more. Finally, they arrived at Corinth (Acts 18:1) where the apostle remained for approximately 18 months (Acts 18:11). During his stay, he stood before Gallio (Acts 18:12-17).

3. Fall-Winter 51 CE:

First Thessalonians (at Corinth).

In 1 Thes 3:1, Paul mentioned his loneliness in Athens, expressed in the past tense. Implicitly, he had already moved to Corinth, then wrote his letter from his stay there (Acts 18:1). Timothy remained in Beroea (Acts 17:14) but implicitly returned to Thessalonica to assess the situation, then reported to Paul (1 Thes 3:2-5).

Notice the fierce opposition both the missionaries and the community faced in the city (Acts 17:1-9; 1 Thes 3:3-4). But also note the focus of the eschaton: concern for the deceased (1 Thes 4:13-15) and the instantaneous nature of the Second Coming (1 Thes 4:16) followed by a general ascension into the heavens (1 Thes 4:17). No where does Paul consider, much less condemn, pagan outsiders as the enemy. Such a message would be antithetical to his ministry as "Apostle to the Gentiles." While Paul, his helpers and the neophytes endured suffering, they did not lash out against those who they hoped to evangelize. This fact gives us insight into Paul's kerygma in the early 50's CE.

4. Paul's Return to Jerusalem

Paul sailed to Caesarea via Cenchreae (where he made a vow; Acts 18:18) and Ephesus (Acts 18:19-20). He arrived in Jerusalem for Passover (Acts 18:21-22) then made is way back to Antioch (Acts 18:2). While the trip from Achaia to Caesarea would have only taken a week of sailing, Paul's stop in Ephesus added a few additional weeks. He celebrated Passover in the spring of 53 CE and returned to Antioch by mid to late summer.

F. Paul's Third Journey

Until the final leg of his travels, Acts provided sparse travel details of Paul's third journey. His travels consisted most of overland routes to revisit the communities he established and build upon his work in the region. Establishing a timeline for his missionary travels depended upon his arrest and initial trial before Felix in 57 CE. Although we list the flow of events in a progressive fashion, we ultimately depend upon that first trial to peg the date of the third missionary trip and work backwards to develop its temporal structure.

Except for sailing between Troas and Neapolis (Acts 20:6). Paul made his way mostly overland.

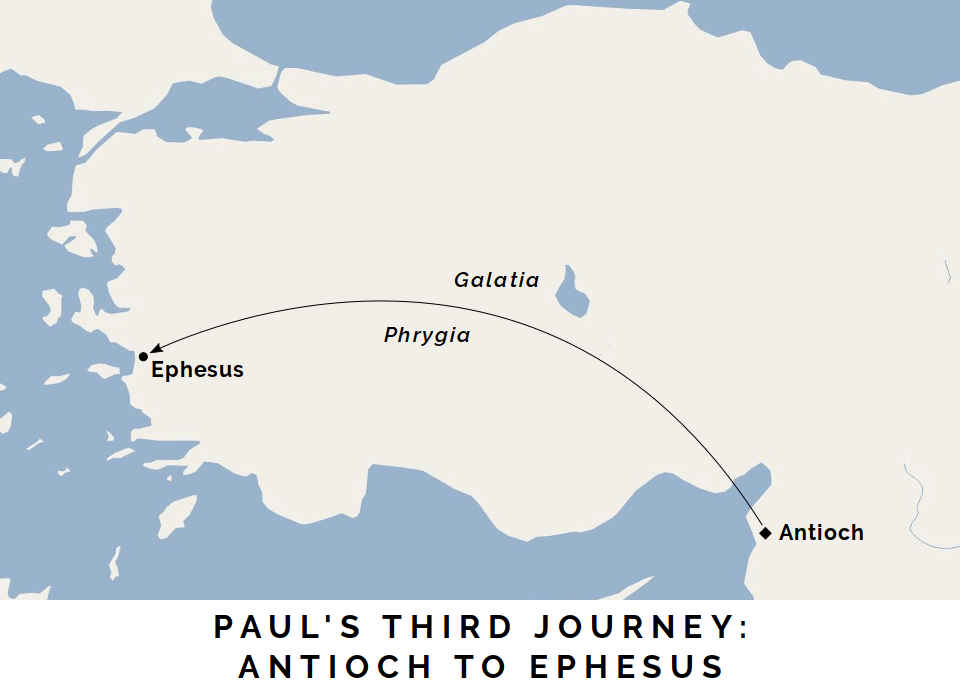

1. Late Autumn to Winter 53 CE:

Antioch to Ephesus.

Paul traveled overland from Antioch to the regions of Galatia and Phrygia. He evangelized there (Acts 18:22-23), thus establishing the community to which he would write his scathing "letter to the Galatians." He continued his journey from Galatia to Ephesus (Acts 19:1). Over 1100 km (680 miles) in length, this leg of the trip took four to six months (seven to nine weeks travel time; three to four months evangelizing in Galatia and Phrygia).

2. Winter 54 CE through Early Autumn 56 CE:

Stay in Ephesus.

In the city, Paul proclaimed the Good News in the synagogue for three months (Acts 19:8), but then faced opposition, so he debated in the school of Tyrannus for two years (Acts 19:9-10). But, according to Acts 20:31, he remained in the area for three years.

3. 55-56 CE: First Corinthians (at Ephesus).

In 1 Cor 16:1-12, Paul expressed his desire to visit Corinth after he made his way through Macedonia; he hoped to arrive after Pentecost for an extended stay. His extended residence at Ephesus (Acts 19:8-10; Acts 20:31) implicitly argued for that city as the locale of authorship. The references in First Corinthians line up with the travel narrative in Acts 20:1-3.

Note Paul's letter addressed divisive issues within the Corinthian community like struggles of leadership, charisms, the nature of the Eucharist, and the teachings of the libertines. The threat of the Judaizers would not raise its ugly head for another year or so. Paul would address it in Second Corinthians (3:1-18), along with the critiques of those opponents (11:1-12:18).

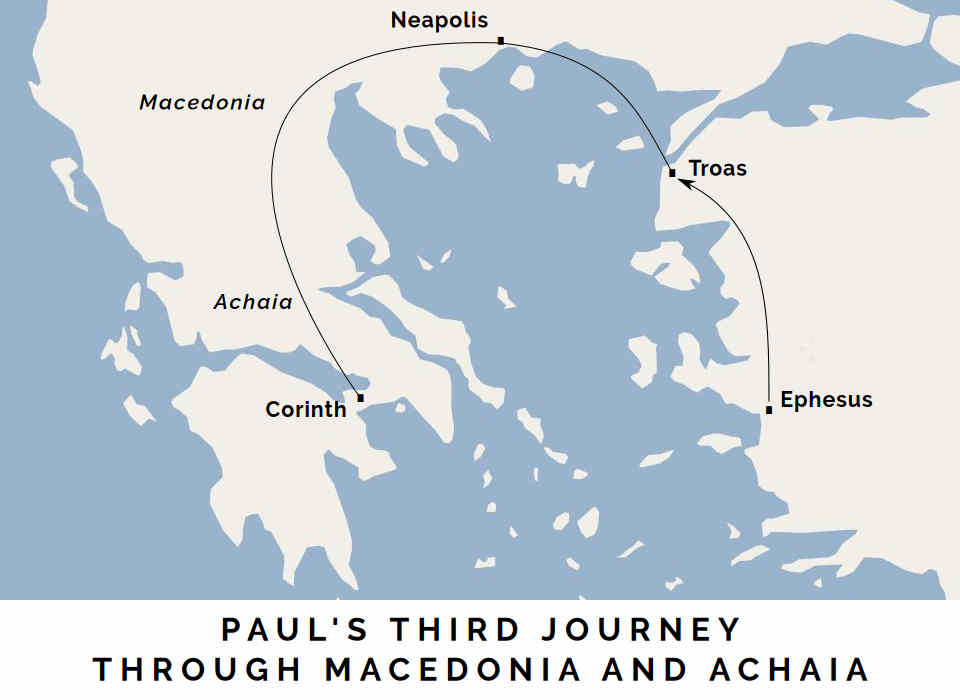

4. Late Autumn 56 CE through Winter 57 CE:

Travels in Macedonia and Greece.

Paul made his way through upper and lower Greece along the Aegean basin, most likely revisiting the churches he established on his second missionary journey. He remained in the area for three months (Acts 20:1-3).

5. Late Autumn 56 CE:

Second Corinthians (in Macedonia).

In 2 Cor 1:16, Paul wrote of his initial intention of visiting the Corinthian community but changed his mind; hence, he implicitly gave a reason for the letter. But he wrote this section of the document after the "Book of Tears" (10:1-13:10) where he threatened to visit them in anger (2 Cor 13:1-3). Added to the fact that Second Corinthians had two distinct chiastic structures (1:3-7:16; 10:1-13:10) divided by an appeal for the Jerusalem collection (8:1-9:15), evidence suggests the apostle wrote two (or three) missives to the Corinthians in short order while he traveled in Macedonia on his way to Achaia (and eventually to Corinth).

Notice Paul's fierce apologia in the face of his critics. These were most likely "Judaizers" ("super-apostles" in 2 Cor 11:22), those who insisted Gentiles convert to Judaism in order to attain equality with Jewish-Christians. He also touched on the subject of Jewish-Gentile equality in 2 Cor 3:1-18; soon, he would develop the subject in Romans and Galatians.

6. Winter 56-57 CE:

Romans in Greece (most likely Corinth);

Galatians (location unknown).

In Rom 15:26-27, Paul referred to the contributions he collected for the mother Church at Jerusalem from the Gentile Christians in "Macedonia and Achaia." This paralleled his travels in the area mentioned in Acts 20:1-3.

The apostle addressed the tension between Jewish-Christians and their Gentile counterparts in the large part of his letter to the Romans. Writing to a distant community about the friction clearly indicated that the compromise of the Jerusalem council did not hold. First Thessalonians did not mention the problem a few years earlier. But, in the intervening half decade, Paul's opponents had spread their message of "a Jewish Messiah for Jew's alone" far and wide. So, he felt compelled to answer their challenge not only to the community in the imperial city (Romans) but to a rural community in Galatia he had evangelized a year earlier (Galatians; Acts 18:22-23). Ultimately, the issue would resolve itself not through intellectual argument but through attrition over time; Jewish-Christians died out while Gentile converts took over.

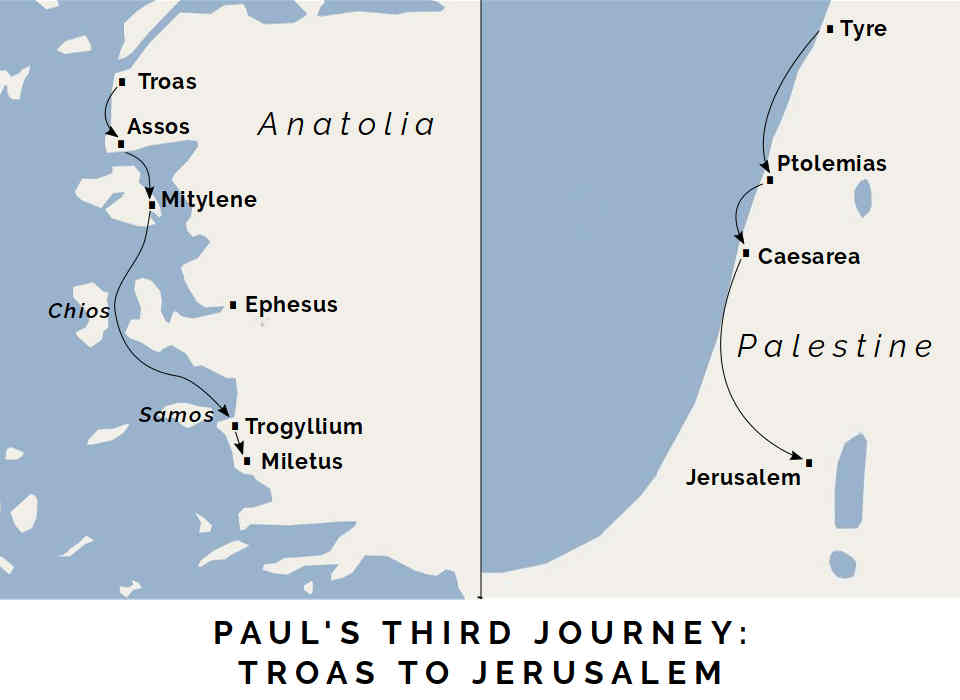

7. Late Winter to Spring 57 CE:

From Troas to Jerusalem.

In Acts 20:16, Paul stated his wish to travel from Miletus (south of Ephesus) to Jerusalem for Pentecost (early summer in 57 CE). His sailing for home began at Troas (Acts 20:6) to Assos (Acts 20:13) to Mitylene (Acts 20:14), then passed Chios and Samos to stay at coastal port of Trogyllium. The next day, he arrived at Miletus (Acts 20:15). After his meeting with the Ephesian community leadership, Paul sailed, making a number of stays along the sailing route (Cos, Rhodes, Patara in Acts 21:1), transferring ships to reach the Phoenician coast (Tyre for a week in Acts 21:2-4), landing at Ptolemias and, finally, Caesarea in Acts 21:7-8. This leg of Paul's third journey took six to eight weeks. Note this "we" section provided much greater detail than the rest of the third journey narrative, arguing for the veracity of the "eye witness" theory.

G. Arrest, Trials and Transport to Rome

1. Summer 57 CE:

Arrest and Initial Trial before Felix.

Paul arrived at Jerusalem to deliver the Aegean basin collection for the mother church. But, he knew full well of the danger involved (Acts 20:22-24, Acts 21:3-4, Acts 21:8-11). Despite his efforts to hue to halahkic demands of Temple worship (Acts 21:26-27), he was accused of heresy and sacrilege (Acts 21:27-28). His opponents claimed he taught Jewish-Christians no longer needed to keep the Law (Acts 21:21) and he would pollute the Temple by bringing a Gentile into the sacred edifice (Acts 21:29). Hence, when Paul appeared, his enemies incited a riot (Acts 21:30) which led to his arrest (Acts 21:31-34). The apostle would have faced torture and even execution for the civil disruption, but he asserted his status as a Roman citizen by birth (Acts 22:24-28). While Paul did face the Sanhedrin (Acts 23:1-9) but had the implicit right to a hearing before Roman officials (Acts 23:10).

So, the Roman commander sent Paul to the governor Felix at the port of Caesarea (Acts 23:23-35). Despite an initial hearing before the governor (Acts 24:1-26), the apostle languished in jail for two years (Acts 24:27) since the official expected other disciples to post bail for Paul's freedom. That payment didn't take place.

Note again the reason for Paul's arrest: civil unrest due to his teachings on ethnic equality before YHWH and devotion to Christ before duty to the Law.

2. Summer 59 CE:

Trials before Festus and Agrippa II

When Paul stood in the court of Festus at Caesarea, he appealed to Caesar instead of returning to Jerusalem in order to face judgment before the Sanhedrin (Acts 25:1-12). When Agrippa II sat in judgment over Paul (Acts 25:23-26:29), he and Festus agreed about the apostle's innocence but, because of Paul's appeal, they were obligated to send him to the imperial capital (Acts 26:30).

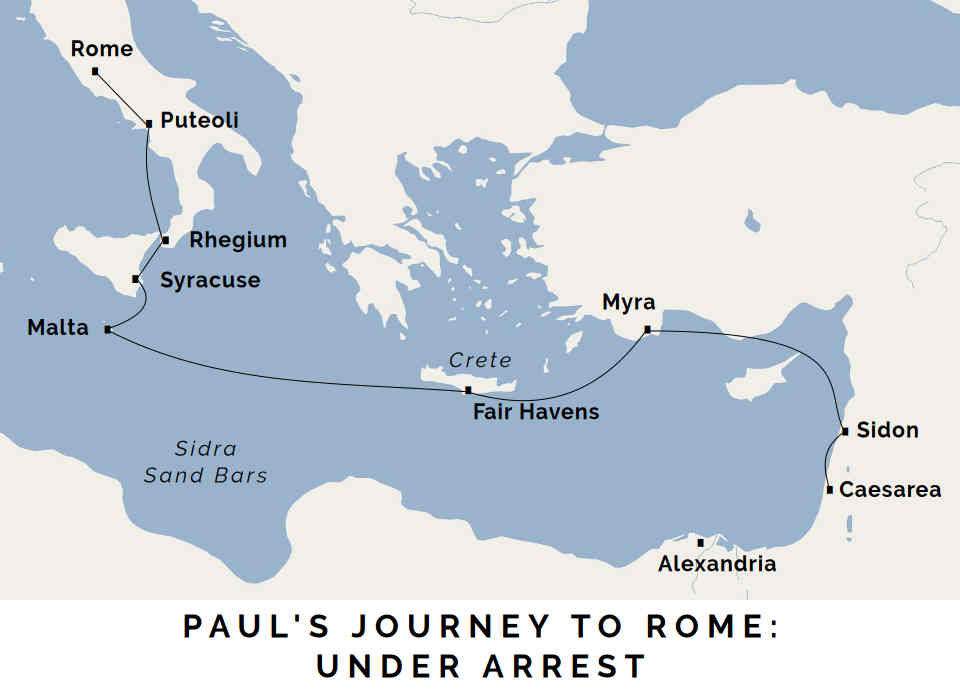

3. Autumn to Winter 59 CE:

Journey to Rome and Imprisonment,

Awaiting Imperial Judgment

Under guard, Paul set sail for Rome, joined by a few companions (Acts 27:1-2). They made their way up the coast, first to Sidon, then west to the Anatolian port of Myra where they booked passage on an Alexandrian grain ship (Acts 27:3-6). Since the late autumn winds would not allow the ship to remain in protected harbor for the winter, they decided to set sail westward (Acts 27:13-15). After two weeks, they beached the ship onto Malta but the violent waves split it in half (Acts 27:27, 39-41). Despite the wreck, all were saved (Acts 27:44).

After enjoying the hospitality of the Maltan leader for three months (Acts 28:7-10), Paul, his guard and his companions set sail on another grain ship. They stopped at Syracuse and Rhegium before landing at Puteoli where a group of disciples met them. From there, they traveled overland to Rome (Acts 28:11-14). Paul was held under house arrest but was allowed visitors including the Jewish leadership of the imperial capital (Acts 28:16-29). The book of Acts ended with Paul continuing his ministry under guard in a rented house for two years (Acts 28:30-31; note that the "rented house" timeline did not infer an end to his incarceration after that point).

Even with the end of Acts, we can still surmise the source of a few letters while Paul was under house arrest.

4. 60-61 CE:

Philemon, under House Arrest in Rome.

Paul wrote a personal but not necessarily private letter (Philemon 1:2) to Philemon, the owner of a runaway slave, Onesimus. With a mixture of guilt (Philemon 1:8, 19) and praise (Philemon 1:4-7), the apostle wrote the missive to shame the owner into taking the slave back without punishment. Indeed, Onesimus was industrious and dedicated to the Christian cause (Philemon 1:15-17) thus a valuable worker in the missionary effort; he did not deserve the wrath of Philemon's anger.

Several details argue for the authenticity of Philemon. Paul wrote the letter in prison (Philemon 1:1) from a mature viewpoint (from late 40's through 50's years of age; Philemon 1:9). These two factors argued for imprisonment in Rome at or after the end of Acts. Note the fact he lived under guard and his age implicitly corresponded with other details of his life in Acts and other undisputed letters. He initially opposed Christianity (Gal 1:13-14, Acts 7:57-8:3. Acts 9:1-2) but had a vision that led to his conversion (Gal 1:15-16; Acts 9:3-9, 17-22). According to the apostle, seventeen years had elapsed between his change of heart and his meeting with the apostles in Jerusalem (49 CE; Gal 2:1-10; Acts 15:1-31). Thus, if we consider Paul lived under guard in Rome during his mid-50's, he would have acted as the zealous enemy of the Nazarenes in his early to mid 20's and converted in the mid-30's CE. From this point, we can speculate he was born between years one through ten CE.

Another detail that argued for the authenticity of Philemon: literary style . The vocabulary and construction of the missive match those of the undisputed letters.

5. 60-61 CE:

Philippians, under House Arrest in Rome.

Paul wrote several letters from Rome to the community at Philippi. Scholars posit the hand of a redactor based upon materials against Judaizers (Phil 3:1-4:1) added to an already structurally whole letter (ABCDCBA chiasmus in 1:1-3:1a). Paul also introduced the letter carrier to the community (Epaphroditus; Phil 2:25-30) then thanked the community for their material support through the same carrier (Phil 4:18). Finally, the letter contained multiple closings (Phil 3:1, Phil 4:2-9, Phil 4:21-23).

Details in the letter point towards Rome. He lived under "imperial guard" (Phil 1:13) and commented on the growth of the faith in the imperial household (Phil 4:22). And, like Philemon 1:9, he commented on his mature status (Phil 2:17).

Despite the confusing jumble in the letter, its literary style and thematic content (opposing the Judaizers) corresponded to that of other undisputed epistles. However, one passage stood out that pointed towards a remarkable development in Christology, the Kenosis hymn of Phil 2:6-11. In these verses, worshipers at Philippi praised a pre-existent Christ ("living in the form of God" in Phil 2:6) who "emptied" himself ("in the form of a man" and "a slave" in Phil 2:7), died on a cross (Phil 2:8) and was raised up to the highest place in creation so all would worship him (Phil 2:9-11). This concept far outstripped any previous notions of the Messiah by early Christians and marked a turning point in the growth of Christian thought, later developed in the Gospel of John. It also indicated a later date of authorship.

6. 60-70 CE:

Colossians, either under house arrest or by a disciple.

Some scholars question the authenticity of Colossians. True, it did share the imprisonment language with Philemon (Philemon 1:1, Philemon 1:9-10, Philemon 1:13, Col 4:3, Col 4:10, Col 4:18) and a list of the same characters (Philemon 1:1, Philemon 1:10, Philemon 1:24 and Col 4:7-17). However, these scholars dispute the some of the vocabulary might not be Pauline. But, most telling, the letter did not share any of the core Pauline themes. Instead, it revealed a development of Christological thought in its "liturgical hymn" (Col 1:15-20) that placed the Christ in a higher ontological status than the Kenosis hymn of Phil 2:6-11. Beyond the pre-existence of the Messiah (Phil 2:6), the Colassian hymn asserted that he was a divine icon and first born, not only of the dead, but of creation itself (Col 1:15). He was directly involved in the formation of the cosmos (Col 1:16-17) and its salvation through his transcendent "fullness" (Col 1:19-20). This language matched the later compositions of Hebrews (Heb 1:1-4) and John's Gospel (Jn 1:1-18).

However, many scholars maintain the authenticity of Colossians based upon the general commonality in writing style between it and the undisputed letters. They also point to verses in these unquestioned epistles that indicate an evolution of Christological thought instead of a revolution (Rom 8:29, 2 Cor 3:18, 2 Cor 4:4-7).

Despite the controversy between scholars, Colossians was written either by Paul or a close disciple in the 60's CE based upon its relationship with Philemon and its development of thought beyond that found in Philippians.

H. Beyond Imprisonment?

At this point, we can only speculate beyond Acts 28:30-31 and the prison letters. Some developed the thesis that Paul was released in Rome and continued on a fourth missionary journey to Spain, based upon Paul's comments in Romans:

...whenever I travel to Spain, I will come to you. For I hope to see you on my journey, and to be helped on my way there by you, if first I may enjoy your company for a while…

Romans 15:24

and a cryptic comment in the post-apostolic letter, 1 Clement:

After preaching both in the east and west, (Paul) gained the illustrious reputation due to his faith, having taught righteousness to the whole world, and come to the extreme limit of the west, and suffered martyrdom under the prefects.

1 Clement 5:5-7

Later Church Fathers would support this thesis. However, despite the weight of tradition, this thesis was speculative at best since it lacked multiple attestations or some harmonization of sources.

IV. Disputed Letters

A. Late First Century CE (70-100 CE):

2 Thessalonians

Scholars dispute whether Paul wrote Second Thessalonians quickly after First Thessalonians or an anonymous writer penned the letter towards the end of the first century CE. While both letters did share the same chiastic structure and similar greetings, they diverged on their closings, the place of Christ in salvation, sudden shifts in themes and vocabulary. The greatest differences between the epistles lay in their eschatological outlook. As I pointed out above, First Thessalonians focused upon the fate of the faithful at the end of time and said nothing about that of non-believers (1 Thes 4:13-17); Paul took this tact in order to evangelize the Gentiles.

Second Thessalonians, however, zeroed in upon the eternal destiny of opponents (2 Thes 1:5-9) and the time frame leading up to the Second Coming (2 Thes 2:1-12). This included the "Man of Lawlessness" who would reveal himself in the Temple as a god (2 Thes 2:3-4). The rise and fall of this evil (2 Thes 2:6-12) paralleled that of the beast in Revelation (Rev 13:11-18, Rev 17:15-18). Both figures pointed towards the Emperor in the latter part of the first century CE.

No doubt, the apocalyptic sentiments found in Second Thessalonians existed throughout the first half of the first century CE among pockets of Jews. The Essenes held such views in the War Scroll (1QM; 30 BCE to 30 CE), a text that explicated both their negative view of the Romans (the "Kittim") and their tactics to defeat imperial troops. However, the question remained: did Paul of Tarsus adopt a similar view against the pagans and their leader when he dedicated his life to their evangelization? While he lived in an era filled with apocalyptic fervor directed against outsiders, he did not adopt such an outlook. In spite of fierce opposition, he based his entire identity in one phrase: Apostle to the Gentiles.

For these reasons, I hold Second Thessalonians was written in the latter part of the first century CE.

B. Late First Century CE (70-100 CE):

Ephesians

The letter to the Ephesians summed up many themes found in other Pauline epistles, especially in Colossians (high Christology, evolution of church offices and the Church's self understanding). Indeed, it built upon the liturgical hymn (Col 1:15-20), connecting Christ's ascendant omnipresence with the Church, as the "Body of Christ" (Eph 1:22-23).

While the author identified himself as "Paul in chains" (Eph 3:1, Eph 4:1, Eph 6:30), he never referred to himself as an apostle, even treating the apostles from an implied distance, even in the past. He also treated the tension between Gentile and Jewish Christians as a resolved issue (Eph 2:11-12).

Differences in writing style between Ephesians and the undisputed letters also indicate authorship in the later part of the first century, after the publication of Colossians.

C. Mid-Second Century CE:

Pastoral Letters

Many scholars hold First Timothy, Second Timothy and Titus were written well into the second century CE for thematic, as well as stylistic, reasons. Four themes stood out: 1) internal, not external pressures, 2) stable social situation for the Christian clan, 3) a development and solidification of church offices and 4) threats that dovetailed with the growth of pseudepigrapha (especially Gnostic literature dating to 150 CE). These themes made a far better match a century after the death of Paul than in his waning years, languishing in jail.

V. Conclusion

The Pauline letters, undisputed, disputed and questionable, comprised a remarkable corpus attributed to a remarkable man, one who fought for the equal spiritual status of those who devoted themselves to Jesus of Nazareth. He traveled thousands of miles, endured hardships and imprisonment for his Lord and the faithful. He or others under a pseudonym of "Paul" provided details to the early life in the churches, the growth of ministry in those communities and their growing awareness of the Jesus they revered and worshiped. The influence of those epistles still reverberates today, even in secular culture. Without Paul of Tarsus, Christianity would not be the world religion it is today; without him, we would live in a far different place.

Photo Attributions

St. Paul portrait. Rembrandt [Public domain]

Fragment of Delphi Inscription. Gérard [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)]

Conversion of St. Paul. Caravaggio [Public domain]